Here at Mezcalistas, we can get pretty deep into the weeds. And while we’re wondering how fermentation tanks might influence the flavor of mezcal, we sometimes forget that–for many people–the more crucial questions are: “How is mezcal different from tequila?” or even “What is mezcal?” These aren’t stupid queries. The answers are complex, which is why our 101 Guides to the different types of mezcal are long and detailed. But if you’re wondering why some mezcal is not called mezcal (but don’t have time to read six pages on the topic), or how tequila became tequila, we’ve created a cheat sheet for easy reference.

Mezcal

Colloquially, mezcal means any spirit distilled from the cooked core of the agave plant. Many varieties of agave can be used–each imparting a different flavor profile to the mezcal. Broadly speaking, the agave is baked, crushed, fermented with water, and then distilled. In most of Mexico’s 31 states, someone is making a spirit from agave and calling it mezcal. Like “wine,” mezcal is a very broad term. But the traditional definition of mezcal is different from the modern legal definition of mezcal.

According to Mexican law, a spirit labeled as mezcal must be made in specific parts of Mexico and by specific production processes, which vary according to the three official classes of mezcal: ancestral, artesenal, and “just plain mezcal.” Each class carries a different definition of acceptable production methods, with ancestral mezcal being the most old-fashioned and the “just plain mezcal” class leaving leeway for industrial processes. For example, agave for ancestral mezcal must be baked over coals in a pit and crushed with a mallet or a stone wheel, while the two other classes allow the use of mechanical shredders and various types of ovens. For much more information, visit our Mezcal Encyclopedia or check out Mezcal 101.

Flavor: Trying to explain what mezcal tastes like is more or less like trying to define the flavor of “wine” as a category. Mezcal has a reputation for being smoky, but that’s not always true, and it’s not the full picture. We prefer the word roasted–which reflects how the agave is cooked. The vast array of agaves used to make mezcal each impart different flavors, as do myriad production processes. That said, most mezcal is not aged in wood, so the flavor is typically defined by agave–not by the sweetness or caramel notes imparted by resting in a barrel.

Tequila

Tequila was once just a mezcal made in and around the town of Tequila, Jalisco. It was distilled from the fermented juice of various types of agave and was known as vino mezcal de Tequila. Due to complex economic and political factors (and a great deal of determination), producers in Tequila were able to gain a toehold on the international market. As the reputation of mezcal from Tequila grew, the name was shortened to just “tequila.” Meanwhile, producers met increasing demand by building bigger distilleries and industrializing their production. The advent of steam ovens, roller mills, and column stills altered the nature of tequila, creating a spirit that now tasted different from traditional mezcal.

The concept of tequila as a distinct category was formalized in 1949, when a new law defined tequila as a product of the state of Jalisco. The definition has changed–for better or worse–over the years. In 1974, tequila got its own denomination of origin (DO). This means that, like scotch and cognac, tequila is specific to one country–in this case, Mexico. Most tequila still comes from Jalisco, but it can be produced in specific parts of four other states: Guanajuato, Michoacan, Nayarit, and Tamaulipas. These days, tequila must be distilled from fermented blue agave, but other sugars may be added during fermentation. Tequila that isn’t augmented with other sugars will be labeled 100% agave. Both categories of tequila may also legally include additives that shape flavor and mouthfeel. The spirit has five classes: blanco, joven, reposado, añejo, and extra añejo.

Flavor: Because most tequila is made from the same type of agave, the flavor profile is more easily generalized than mezcal. However, a significant spectrum of profiles is shaped by aging or the difference in terroir between regions in the DO, as well as wild variations in quality. An old-fashioned blanco might have a bright agave-forward flavor with notes of mint while some of the bigger brands are so laden with additives that their blancos taste like melted frosting. Meanwhile, an extra añejo can taste more like a brandy than a blanco tequila.

(For a better understanding of tequila controversies, check out our articles on the clash between agave farmers and “big tequila,” and our coverage of the class action lawsuits against liquor giant Diageo.)

Bacanora

Bacanora is a regional mezcal from the state of Sonora, in northern Mexico. Like all mezcal, the spirit is distilled from the roasted and fermented heart of the agave plant. But because Sonora is outside of the denomination of origin (DO) for mezcal, it can not be labeled as such. It has its own legally defined region and name.

Like other types of mezcal, bacanora must be 100% agave. Unlike other types of mezcal, the law dictates that bacanora must be made from one type of agave: A. angustifolia haw. Bacanora does not have “ancestral” and “artisanal” categories, but it does have four classes: blanco, oro or joven, reposado, and añejo. (Blanco is by far the most common.) For much more information, check out What is bacanora? or this article about women in the bacanora industry.

Flavor: If we’re speaking in broad generalizations, bacanora is an accessible category that tends toward sweetness and big, rounded flavors. A complex bacanora can have a pleasing candied note that doesn’t obscure vegetal undertones.

Raicilla

Raicilla is a regional mezcal made in the state of Jalisco, in western Mexico. Raicilla has its own denomination of origin, which dictates it may be produced in two distinct regions: along the coast around Puerto Vallarta and in the mountains around the town of Mascota. Raicilla must be 100% agave. Historically, many types of agave have been used to make raicilla, and that continues to be the case. That said, mountain raicilla is primarily distilled from A. maximiliana, commonly referred to as lechuguilla, while coastal raicilla is typically derived from varieties of A. angustifolia and A. rhodacantha.

Raicilla got its DO in 2019, making it the latest addition to the official pantheon of Mexican agave spirits. Specific production standards and categories have been established, but have not yet been approved by the federal government. Aged raicilla exists, but the blanco is most common and most people consider it “traditional.” For much more on raicilla, check out Raicilla 101 and Raicilla Rising.

Flavor: Raicilla is probably the least accessible regional mezcal, which can translate to interesting for those of us who enjoy unusual flavor experiences. That said, not all raicilla is “funky.” Coastal raicilla can be notably floral, fruity, and acidic while raicilla de la sierra, or mountain raicilla, sometimes has a piney character.

Destilado de agave

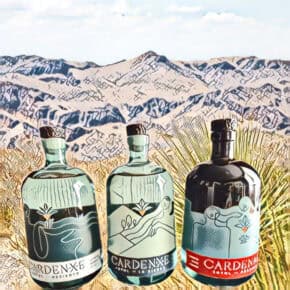

As you may have guessed, destilado de agave translates to agave distillate. These days, numerous reputable producers have opted out of the certification process that is required to label a mezcal as mezcal. Instead, these brands are labeled as a destilado or agave spirit.

This doesn’t mean that the shelves of your liquor store are stocked with unregulated agave products. Destilados are regulated–they just aren’t required to meet the very specific standards dictated to be certified as mezcal, tequila, raicilla, or bacanora. This doesn’t mean that destilados are inferior. Why do brands opt out? Read more.

Flavor: There is no common flavor profile because destilados are from all over Mexico, use various agaves, and may or may not share production styles. A bottle labeled as a destilado could contain any type of agave spirit–including tequila. (You should be able to tell what type of spirit is in the bottle based on where it’s made and the type of agave. This cheat sheet could come in handy!)

Vino

Although vino literally means wine, “vino de mezcal” or “vino mezcal” is an old-fashioned way of describing agave spirits. This stems from an older usage of the word mezcal–which refers to the agave plant rather than the booze made from it. In some parts of Mexico, particularly rural areas, people still call mezcal “vino” and agaves “mezcales.” We see this echoed in the word vinata, which means distillery in some regions. Note: Sometimes vino may have another descriptor—for instance, raicilla from the mountains may be called “vino de cerro,” which means “wine from the hills.” Read more.

Flavor: Again, vino can refer to any type of spirit so there’s no common ground, other than alcohol.

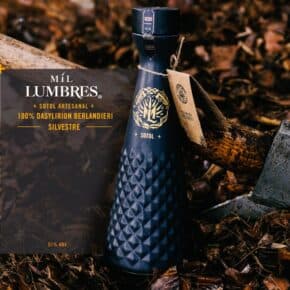

Sotol

Sotol is not mezcal, but the production process is similar and shares historical roots. Instead of agave, the spirit is distilled from various varieties of the Dasylirion genus, usually Dasylirion wheeleri. These spiky plants are commonly called sotol in Spanish and desert spoon in English. Most sotol comes from the northern state of Chihuahua, although the denomination of origin allows production in Durango and Coahuila. Read more.

Flavor: Sotol tastes something like mezcal–but not quite. The profiles can range from vegetal sweetness to the duff of a forest floor.

I was under the impression that stone wheels were NOT allowed in ancestral mezcal production, and in addition, MUST be distilled in a clay pot. Crushed by hand mallets and zero ‘industrial’ help, which a tahona would technically be.

Hi Justin. Thank you for reading and engaging! The norm has the following to say on this process in production: “Molienda: con mazo, tahona, molino chileno o egipcio.” It goes on to say that it must be distlled in clay with a montera of wood or clay.

Even though I’ve read numerous articles about mezcal, these distinctions were never clear to me. Thanks for the excellent “distillation!”