When we first pull up to the Chacolo distillery outside of Zapotitlán del Vadillo in southern Jalisco, we think we’ve interrupted a tour because the parking area is full, a bottle of mezcal and a constellation of glasses are set up in the tasting area, and cook fires are burning in the outdoor kitchen.

As it turns out, the parked trucks all belong to the Partida family. We’re here to interview Miguel Angel Partida Rivera, but most of his nine siblings work for the family business, and his mother Doña Margarita and father, maestro tabernero Don Macario Partida Ramos, are also on site.

Miguel Angel is a fourth-generation tabernero. His great-grandfather and grandfather were workers at distilleries where they rented time to make their own mezcal. In those days, the tabernas were clandestine and subject to raids from the tax authorities, who would pour gasoline into the fermentation tanks and set fire to the stills. Despite the harassment, the taberneros persevered.

“Eventually my grandfather started to distill and sell his own mezcal,” Miguel Angel says. “By the time my father began working in the industry, the president of the Republic had changed the law, and they were given a permit to distill. So we came here and built a taberna.”

Although Chacolo is a legal distillery, the mezcal is classified as a “destilado de agave” because their region is outside of the Denomination of Origin for Mezcal (DOM). And though the Partidas are not legally able to label their mezcal by its proper name, savvy consumers know better. Chacolo has been reaching a wider audience since their 2019 partnership with Heavy Metl (which also imports such highly acclaimed spirits as Caballito Cerrero, Rey Campero, and Real Minero). The spirit is now available in 20 US states.

The family is gaining recognition abroad both for the superb quality of their mezcal and for their attention to sustainable agricultural practices. While Miguel Angel estimates that about 50 percent of the agave in their region is grown for tequila, the family eschews monoculture in favor of mixed fields. They grow 16 varieties, mostly A. angustifolia, but distinct in their sugar levels, flavors, and aromas. This diversity allows them to play with permutations and regularly release new blends.

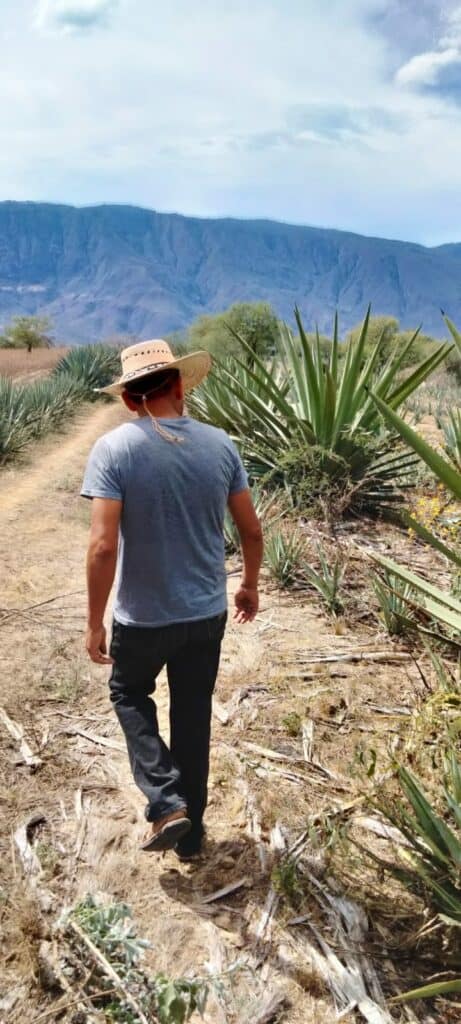

Our interview begins in the fields. As we walk amongst enormous agaves, Miguel Angel points out the differences that identify each varietal—most of which would seem miniscule to the novice. Although Miguel Angel works primarily in sales and events for the brand, he speaks with an easy familiarity and palpable affection for the plants. “Here we have a cimmaron, and here we have a brocha. You can identify the brocha [a variety of A. angustifolia] because the teeth of the spines are taller. We say that it’s toothier.”

As Miguel Angel talks, we pass two of his brothers, who are hard at work with machetes. Beyond the fields, a wall of mountains, the Sierra de Manantlán, rise to hot blue skies. I seek momentary relief in the shadows of a big agave.

“The Azul Telcruz is the sweetest of them all,” Miguel Angel says. “The least sweet is the Ixtero Amarillo, but the advantage of the Ixtero Amarillo [a variety of A. rhodacantha] is that it has something more intense. It’s not as aromatic but it’s more intense. They each have their advantages.”

Speaking of advantages, the Partidas have been able to sever the quiotes of Ixtero Amarillos and then allow the resulting capónes to mature in the fields for four more years—quite a feat when we consider that capónes are vulnerable to pests and one year of further maturation would typically be considered better than average. It seems possible that the Partidas’ clever regime of organic pest control may be responsible for their remarkable success with capónes. Whatever the case, the resulting mezcal is as intensely rich as you might imagine.

Although Miguel Angel gives all the credit to the hardy variety, it’s clear he views sustainable practices as the foundation of their work.

“We don’t use pesticides or herbicides because we don’t want to contaminate the soil. Everything is natural…We can’t get rid of the pests completely, but we control them.”

Their natural methods are diverse. To repel pests, they apply chile and garlic and treat the plants three times a year with a mixture of water, ash, and lime (the mineral). They also create traps using a mixture of agave and sugar to lure insects away from the living plants.

Beneficial animals are a key part of the regime. The fields are dotted with mesquite trees that attract birds, which feed on the beetles and other pests. The family’s practice of growing corn, tomatoes, squash, and chiles amongst the agave serves to attract a healthy population of mice, iguanas, and rabbits that either eat weeds or beetles and other pests. Burros and cows also help with weed control.

Miguel Angel gestures across the valley to a field of blue agave growing in neat but barren rows.

“If you look at the blue agave fields, you’ll see there are no trees. So the animals have nowhere to hang out. The [tequila] industry is displacing plants, birds, and other animals, and what we want to do here is conserve everything in harmony.”

He tells us that they wouldn’t be able to grow vegetables in abundance if they were constantly depleting and poisoning the soil through industrial agricultural processes.

“It’s more work, though,” he says. “But in this way, we have everything—agave and food. We used to run it like a business, and we’d sell half the corn. But not anymore—The price of corn is too low right now so it’s not worth it for us to sell it. Instead, we consume all the corn we produce.”

Their stance against chemicals may be strong, but they’re still at the mercy of nearby farmers who don’t share their philosophy. Miguel Angel says that diseases and infestations have increased as more neighbors engage in conventional monoculture. “The pests return in force after fumigation and also jump over to neighboring fields,” he says, gesturing to their own lands.

To increase biodiversity and guard against plagues, the family grows agave both from clones and from seed. Miguel Angel says growing from seed was challenging at first, but now they’re on a roll with it.

“There are advantages and disadvantages to each method,” he says with a shrug.

As we walk toward the taberna, Miguel Angel points out a giant organ cactus he says is over 200 years old. The current distillery is rather new, though built in the traditional open-air style. All the usual elements are in place, but every aspect has a kind of rustic elegance that seems to indicate a very specific vision.

The mortared stone roasting pit is so beautifully built that it could masquerade as a sculpture at a modern art museum, and the floor of the taberna is cobbled with small volcanic stones.

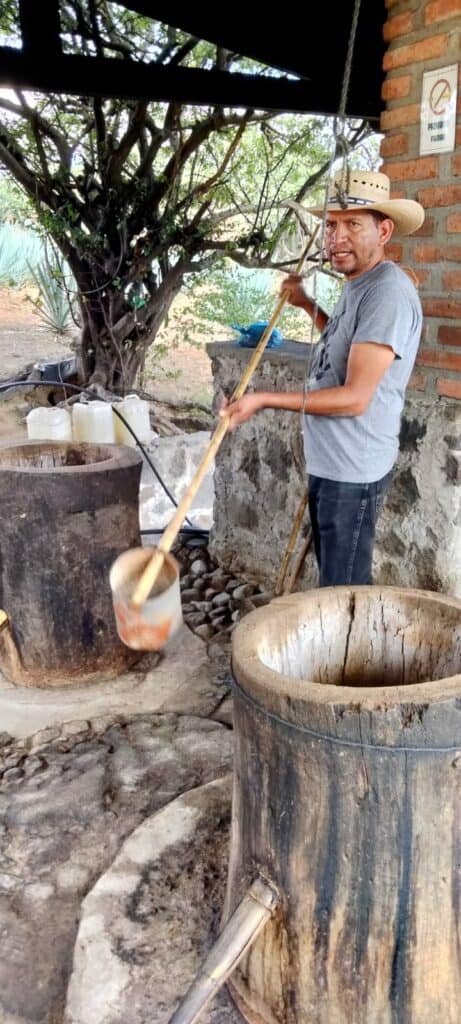

We look at a series of wooden tanks or tinas, where the Partidas typically ferment roasted agave for three or four days unless the weather is cold. They also use stone and mortar tanks sunk into the ground like wells. Again, their practices are natural. “The yeast blows in on the breeze, arrives, and ferments,” he explains.

Chacolo is double-distilled in wood-fired Filipino pot stills carved from darkened tree trunks (parotta) and augmented with copper condensing pans and spouts made from pencas, or agave leaves. In this time of drought, the Partidas have created a closed circuit system for the condenser–the water feeds back into a tank and is used over and over.

In the neighboring state of Colima, the agave spirits of southern Jalisco are often referred to as Tuxca, which has resulted in proposals for a controversial new Denomination of Origin (DO). But maestro Don Macario is emphatic that the producers themselves have always called their spirit vino de mezcal. It is likely one of the oldest mezcal traditions, a direct descendent of the coconut distillate that was introduced to the region by Filipino sailors who worked the Spanish trade route between Manila and what is now Mexico.

Although the family adheres to traditional practices, Miguel Angel says they’re always learning. They consulted an agronomist on how to better grow agave from seed, and three years ago they implemented a process to transform vinazas, the acidic waste from the distillation process, into compost for growing more agave and corn.

We get to sample the products of both plants over lunch. It turns out the cook fires were burning not for a tour group but for me, my companion, and the family. We eat outside with Don Macario, Miguel Angel, and his brother Salvador, in the shade of a huge tree. The table is laden with carne asada, homemade blue corn tortillas, beans, and two big molcajetes of salsa.

When I ask the maestro what makes the mezcal of their region so highly esteemed, he reflects, “One thing is that we make purely mezcal from the river water. The other is that we don’t adulterate or add sweeteners. Another thing is that we use many varieties of agave—some people only use one or two, but we use many. Maybe that’s what makes us famous.”

After lunch, we share a glass of this famous mezcal, in this case their Lineño (a variety of A. angustifolia). The Partida’s dedication to every aspect of the craft comes through in the final taste. Spicy with floral and citrus notes, the spirit seems simultaneously fierce and delicate.

“It’s our family heritage to make mezcal,” Miguel Angel says after taking a sip. “My father taught us, and we hope that our children will learn as well so that we can continue the tradition.”

He says the fifth generation is involved. The kids help out when they can.

“There’s no recipe for making mezcal,” he reflects. “You learn it, you get involved–everything is empirical. It’s interesting that this is ancestral knowledge. We don’t want to lose that. We want this to go on.”

The Chacolo slogan, “Cual Debe Ser,” says it all. This is how it should be.

Correction 4/30/24 – photo removed that incorrectly identified a stone lined pit as a fermentation tank.

Very informative and a portrait of cultural legacy most visitors to Mexico would not see.

I was temporarily transported and enlightened in one article ! A tribute to great writing and photos . Keep up the great work .