Michoacán is a devastatingly beautiful place. It’s no wonder why Dianna Kennedy chose to make the state her home. Lush tropical forests meet the magical Lake Patzcuaro and the city of Morelia hides wonderful cultural expressions and culinary treasures. Michoacán is where carnitas were created and can still be savored from vast copper pots at roadside stands. It’s where those vast copper pots continue to be made. It’s the home of cotija cheese and charanda. The state’s most well-known export is avocados, but, thankfully, it also continues to produce mezcals like Hacienda Oponguio.

In Michoacán, many ambitious producers are creating beguiling flavors, but these mezcals represent a tiny percentage of the export market. The mismatch between market and production reflects ongoing tensions with the Oaxacan goliath and Mexican politics.

Hacienda Oponguio is a mezcal from Michoacán that embodies so much about the contemporary mezcal world. It’s a small family brand that can trace its tradition through generations, but the people who run the show today are newer to mezcal–though they’re passionate converts.

It all starts with a family history.

Like many family mezcal sagas, the story of Hacienda Oponguio is at least 100 years old. Juan Manuel Mejía Leal, who heads Hacienda Oponguio Mezcal, says that his great-great grandfather was making mezcal in the area with his son, but stopped because local prohibition made it too dangerous. He was almost caught by authorities and stopped distilling. The tradition was completely cut short.

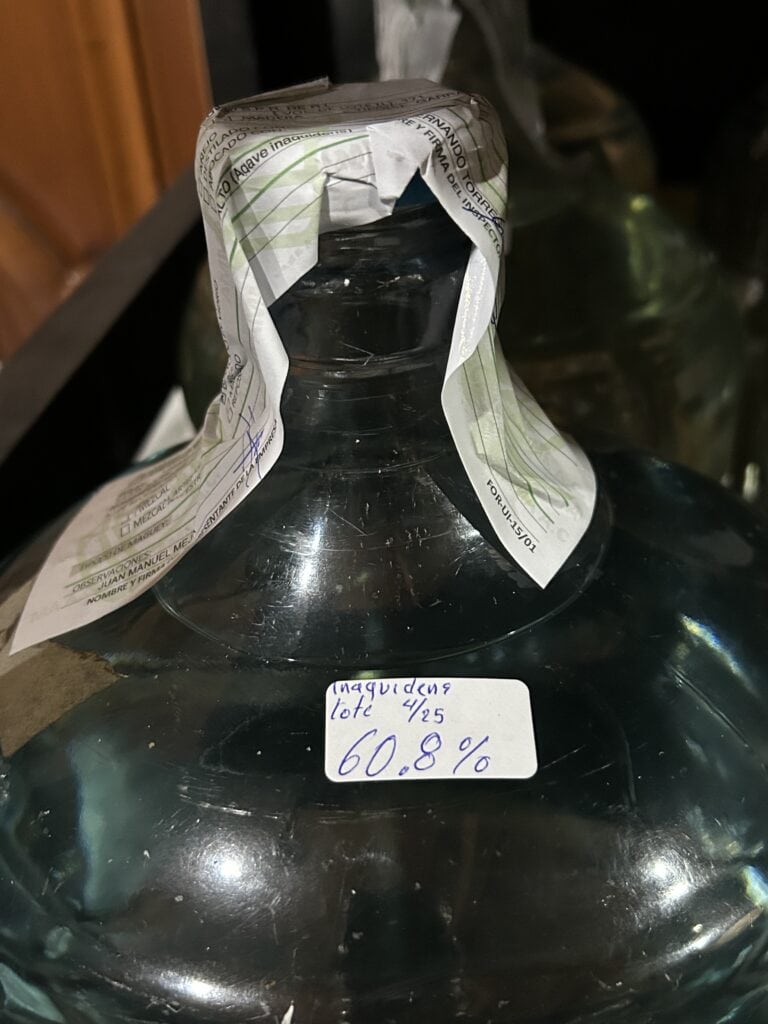

Juan Manuel’s great aunt Emma Mejía Contreras fondly remembers her father “loading the demijohns on horses to go deliver the mezcal.” The time scale may seem enormous, but Emma Mejía Contreras is still alive–she just turned 90 and, according to her great-nephew, “She still loves to drink mezcal.”

That sense of scale is endemic to the mezcal world. Michoacán was probably one of the first mezcal producing areas in what we now call Mexico. Filipino sailors on Spanish galleons brought portable stills to Western Mexico. The distilling technology spread from the ports and out through the contemporary states of Guerrero, Jalisco, Colima, and Michoacán.

A new vision

That brings us to the present-day story of Hacienda Oponguio Mezcal. While definitely rooted in Michoacán, where the family once owned an estate called Hacienda Oponguio, today’s brand has a much more recent lineage. Don Juan Manuel Mejía Hernández, the grandson of the original creator of Oponguio, started making mezcal in the 1990s because he had never lost the taste for it. His son Juan Manuel told me, “He always liked taking his mezcal produced in Oponguio to share with friends at gatherings or parties.”

This revitalized mezcal was derived from inaquidens agave from the family ranch, produced in tiny batches two or three times a year, and was entirely for family use. Don Juan had essentially recreated Hacienda Oponguio Mezcal as a hobby for his family and friends. He realized that if it was going to be a business, he’d need someone else to take it to the next level. That’s when he talked to his son Juan Manuel about it. At the time, Juan Manuel was working in an office. He wasn’t a distiller. He knew very little about mezcal but he looked at the business and said “I’m interested, but if we’re gonna do this, I’m gonna do it my way.”

Usually, this is where we cue the Frank Sinatra version of “My Way” and slide into a well trodden (and just as frequently true) story about how a mezcalero recovered a tradition and has kept doing things exactly the same way as his grandfather, his father, and everybody before them. But just as frequently, probably much more frequently than most people think or like to mention, contemporary mezcaleros are innovating and adding to the tradition that they received. And that’s exactly what Juan Manuel did.

In 2018, when his dad gave him the call about making Oponguio into a business, Juan Manuel decided that he was going to make mezcal in a completely empirical way. He wanted to look at exactly what happened in the distilling process, understand every aspect of the ingredients and processes, in order to be able to manage all the variables to produce something that he really enjoyed. He started out by examining everything in detail, looking at what other distillers were doing, interviewing the chemists at the then CRM (today Oponguio is certified by AMMA), whom he credits as wonderfully experienced guides to the science behind mezcal because, as he points out, “They visit six or seven factories every day.”

Using this empirical approach, Juan Manuel slowly created his own recipes, which are very different from his inherited tradition. It’s his interpreted tradition. He emphasized the importance of slowing everything down to improve aromas and flavors.

“I wanted a very slow fermentation and distillation…Above all, it takes great patience to get something that is of great value,” he says.

Expanding the family business

While Juan Manuel was making wonderful mezcals and laboring over every detail of production, he still needed a partner to actually sell those bottles. And he especially needed someone to do that work in the United States. The traditional route is to find an importer and work with a distributor but, as any mezcal producer can tell you, it’s awfully hard to find a partner now that so many brands are on the market. And that’s where family comes in again. Don Juan asked their American cousins, Mayra Villa and her husband, to import Oponguio.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before, but Villa just jumped in and launched the brand in the US. She quickly realized that she didn’t know the business, but she was excited by the mezcal so she grabbed her backpack and started going store-to-store to sell bottles. As she circulated through the Southern Californian sales landscape, she met more and more people in the business and joined the LAX Mezcal Club. The larger mezcal community opened doors, and a business began to take shape.

Mayra Villa says that community is energizing but what keeps her going is the connection that drinkers make with her mezcal. She works with other small family brands to do tastings. “People see our table and our signs that say ‘mezcal Michoacáno.’ They come and recognize that we’re from Michoacán and say that they didn’t know that Michoacán made mezcal. It’s so positive and also opens the doors for other people.”

Today the brand is available across California, Arizona, Washington State, and most recently New Jersey. Mayra Villa says that they would love to work in other states, but that they’re caught in the same dynamic of many small or mid-sized brands–they can’t find the right partner. She doesn’t want Hacienda Opungio to get lost in a larger portfolio. “We don’t want to be just another brand,” she explains. “We want to work with someone who doesn’t have many brands, so that we can work together and team up.”

She thinks there’s plenty of room for more Michoacán mezcal: “I think there’s always room for everybody to grow. When I came into this industry, this community, I met wonderful people like Salvador (from La Luna Mezcal) and Flor, who were very helpful. Everyone has their unique place, story, product.…”

Mayra Villa continues the tradition of boosting others in the business everywhere she goes. She even co-founded an organization called Amigas y Mezcal to promote small (and woman-led) mezcal brands that frequently don’t get as much promotion as they deserve. Clearly, these communities of blood and chosen families really pay dividends for Michoacán and all its wonderful mezcals.

What’s so different about Michoacán?

Juan Manuel really focuses on bringing the wonders of the Michoacán terroir to life. Most of the Hacienda Oponguio production is made from the local inaquidens but there are different bottlings depending on when the agave is harvested, which means that the brix level varies considerably. The Herbal is made from agaves harvested in the winter–which lowers the brix level and, as the label implies, gives this bottle a much more vegetal flavor. The Frutal was made from inaquidens harvested in the summer with much higher brix levels, which contribute to robust tropical fruit flavors. On a different wavelength, the Seco bottling is made from agaves that grew in the shade, which give it a much dryer flavor. Few other mezcal labels showcase the flavors and aromas that arise from diverse agave growing conditions.

Juan Manuel emphasized that he really likes working with inaquidens. Each of the plants is different because they are naturally pollinated. In contrast, the espadín that he works with are propagated from hijuelos so they’re genetically the same material as their parent plant.

And the inaquidens is a tough customer. As we talked through the details of Juan Manuel’s process, he wanted to impress upon me just how tiny the yield is compared with espadín. He says, “Espadín is easy to produce. For every lot of 1,300 liters of espadín mezcal, we make 200 liters from inaquidens.” He adds that he had to spend quite some time finding a way to deal with the fermentation process because inaquidens tends to foam up in fermentation and distillation–just like jabali. Mastering that process grew out of his empirical approach to distilling–he eventually found a way to keep the foaming from disrupting the process.

Michoacán has an incredibly distinct terroir of hilly jungle where cupreata and inaquidens agaves are cultivated, displaying some of the most diverse flavor combinations in the mezcal world. This inspired Juan Manuel’s approach of highlighting where an agave was grown rather than just the agave itself, especially the inaquidens, which is special because it is so rare and local, but also because it reflects its terroir so dramatically. Oponguio gives us the opportunity to taste what different environmental factors do to an agave.

Juan Manuel also produces angustifolia and cupreata and ensambles–showcasing his ambition and the Michoacán range. The five expressions offer many diversions. There are two ensembles with inaquidens, allowing you to venture further into tasting comparisons. What happens when this agave meets cupreata or angustifolia? Or you can try a pure cupreata.

The new kid on the block is a pure angustifolia that would normally be out of place in the classic Michoacán agave pantheon–but Juan Manuel loves espadín so he wanted to try it out. He made one batch with imported espadín from Oaxaca and a second with locally grown plants. He already has angustifolia planted locally for future bottlings. And, to round things out, Oponguio also offers a cupreata añejo. Coming soon, they will release an otherworldly pechuga. (More on that as soon as it is released.)

Where next?

It’s fascinating to talk to Juan Manuel because, like so many young mezcal distillers, he’s finding his own way in the business through hard experience. While we justifiably love to talk about the almost mythic mezcaleros who have been making this spirit for decades, like Bertha and Don Lorenzo Angeles, a wave of younger distillers is constantly pushing up with new ideas based on their own experiences. Juan Maneul travels to the US to open markets and advance the family brand with his cousin Mayra. Like many of his contemporaries, Juan Manuel is straddling the border between tradition and innovation. These distillers are creating new business arrangements that reflect their self regard and ambitions.

His vinata sits on a hill above Lake Patzcuaro and boasts an amazing view, which you can savor along with a meal featuring local specialities like coronitas, the regional tamal. He and his family obviously cherish these roots but also just as clearly focus on the changing nature of the world around them.

Leave a Comment