To be a successful pioneer in a field takes passion, guts and when you can get it – support from like-minded friends.

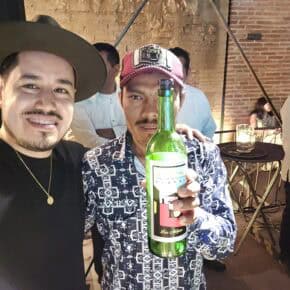

This is the story of three women who share a passion not only for Chihuahua sotol, but also a mission to bring something positive to Ciudad Juárez’s troubled reputation. As Ariana de León succinctly puts it, “I love [my sotol project] because it gives me the chance to generate good news about the area, to demonstrate something good about [Ciudad] Juárez.”

Although pretty much unknown north-of-the-border, their story has been covered in regional and even international press. The most recent story appeared in El Diario of March 2022, who called the three women “the sotol girls.” Perhaps a little sexist, but it does recognize the contribution the three are making.

De Léon, Yaremi Navar Quiñones and Valerie Alcalde Bussey each came to sotol through independent paths, but after finding each other over the years, they consider the mutual support they have developed to be indispensable. After all, they are all working toward the same end, the establishment of a strong national and international market for sotol, big enough not only for themselves but also for the traditional sotoleros, discovered and undiscovered.

Being women has presented both challenges and opportunities. Historically, sotol making and consumption was mostly, if not exclusively, the realm of men, in no small part because it has a “moonshine” past. Sotoleros were persecuted more than even mezcaleros.

This recent history is extremely important for these and other newcomers to sotol because the best makers come from families that have experienced the oppression of their livelihood by both legal and extra-legal means. It means that it takes much more effort to break that initial cultural barrier between a rural producer hidden in the deserts and mountains for generations and “educated city slickers” now interested in partnering with him. Being a woman means that traditional gender roles enter the mix.

Let’s take a look at the three entrepreneurs’ histories.

Ariana de Leon

If there is a leader of this group, it is Ariana de León, who at the tender age of 20 got into the manufacture and sale of the spirit.

She grew up on her family’s Villa de Luz ranch located near the Samalayuca Dunes just south of Ciudad Juárez proper, and even though the Dasylirion plant (colloquially “desert spoon” in English) grew all around them, no one in her family or the area had been making sotol.

De León is unique among the three, not only because she was the first to get involved with sotol, but she and her family are producers of a sotol, which they called 5 Tragos, working under the business name of Casa La Sotolera.

She majored in business administration at Monterrey Tech’s Ciudad Juárez campus, where she was required to start or expand a small business to graduate. While weighing her options, her father came across an article about sotol and wondered if the local varieties of Dasyliroin were suitable for its production. The answer turned out to be “very much so.”

However, it was not simply a matter of gathering and processing local plants. De León had to learn from master sotoleros, and none were to be found in the Ciudad Juárez area. So de León and her father went to Aldama (near Chihuahua city) noted for its desert sotols. It took almost a decade and a half but by 2022, the family was able to set up a complete distillery using local plants at the family ranch.

That distillery is Casa Sotolera with its signature sotol brand 5 Tragos in three varieties: blanco, reposado, and añejo. As the spirit is made 100% of local Dasylirion, they note “The minerals of the ground give the plant’s juices particular flavors – 100% desert.”

But Casa Sotolera is not just a distillery, it is also a weekend retreat that allows visitors to experience the solitary beauty of the desert. “Here there is air, light, space, a sense of freedom you don’t have in the city as you are in the desert – in the middle of nowhere,” says de Leon, “this is a huge attraction for us, along with the sotol.” Some are hesitant to try the spirit at first, but a restaurant, distillery tours and the peaceful atmosphere of the ranch encourages many to go ahead and take that first sip.

De León, so far, has kept both 5 Trabjo and Casa Sotolera a regional family business, although they regularly get visitors from other parts of Mexico and the world.

“It’s something that can only be made here. This is Juárez in a bottle. A taste of our history,” she told The Guardian in 2018. It is not clear if or when 5 Tragos might be more widely available. However, you can contact them via their Facebook page.

Yaremi Navar Quiñones

As much as her career is connected to De León’s, Yaremi Navar has tread her own path from the beginning. She studied gastronomy in Mexico City in the mid-2000s and worked in the restaurant industry. Most of Mexico’s haute cuisine is in the capital, but Navar wanted to promote the regional foods and preparations of her home state of Chihuahua. At the time, building a sotol brand was not on her agenda.

That said, sotol wasn’t exactly unknown to her “…after all, it is strongly connected with the north, is it not?” she notes.

In 2011, she took note of mezcal’s success and wondered what sotol’s chances were. But she knew little about the spirit, not even how to make contact with traditional sotoleros. She began by asking around on social media, and fortunately the state’s secretariat of tourism answered her, recommending that she contact Ariana de León.

That was the beginning of a close professional and personal connection that lasts to this day. De León helped her with those crucial first introductions that would allow her to establish a reputation among the reserved sotoleros.

But Navar’s aim was not to create her own distillery like De León. Instead, Navar and her brothers Jesús and Sergio González Cervantes decided to draw upon their expertise in gastronomy and the sommelier field to find quality sotols to market under a brand that they created and promote – Flor del Desierto.

The first variety, Desierto, was created in 2011, but it took two years to bring it to market. It was a small formal presentation of only 24 bottles at a festival in Mexico City, but they met with critical success.

That acceptance encouraged Navar and her partners, who were working in Mexico City to promote their sotol brand and sotol in general. She already knew the gastronomic scene in the city, plus the capital is a large market which has greatly accepted mezcal with her and her partners expertise guiding them to selecting what varieties to promote. In 2019, the brand won gold at the Brussels World Competition in the distilled spirits category. More recently, it won the Mexico Selection competition in 2023.

The success in Brussels led to a sharp increase in sales and the introduction of new varieties to market. Today, there are five, the original Desierto, along with Sierra, Veneno, Cascabel and Carnei.

Navar emphasized to me that she doesn’t want to take credit that is not hers. She is not a producer, nor does she have any say in how her partner sotoleros make their product. Instead, she is more interested in bringing the original flavors developed over generations to markets sophisticated enough to appreciate them, and that includes resistance to lowering the traditionally-high alcohol content down from around 50%.

Flor del Desierto sotols come from various parts of the state, in particular the renowned sotol producing areas of Coyamé de Sotol, Aldama, and Maderas. Although Navar has worked with various sotoleros over the past years, today she principally works with two: Gerardo Ruelas is in charge of the production of Desierto, Veneno and Cascabel, while José Armando Fernándo oversees the production of the Sierra and Carnei varieties. Their roles are crucial because both bring generations of sotol-making experience with them and have complete control over the final product.

Navar’s role is that of distributor and producer, splitting her time primarily between Ciudad Juárez and Mexico City. Brother Jesús told City Magazine in El Paso that the work “…[is] really cool because they [the sotoleros] are finally getting the recognition they deserve. They’re also finally getting the pay they deserve.”

The 2019 Brussels award was pivotal to the company, allowing it to sell 10,000 bottles, 70% of which were exported. The brand is available in Mexico (especially Mexico City), and you can now buy their sotol in Canadá, the United States, Saint Maarten, Australia, Thailand, and twelve countries in Europe. Navar finds that international acceptance highly gratifying.

Navar recognizes that sotol is still in a transitional stage, much the way mezcal was 15+ years ago, so the future is not yet written in stone. But she is optimistic. In addition to being available in various parts of Mexico, they have participated at several Mezcalistas events and are perhaps the best-known sotol in the US.

Valerie Alcalde Bussey

The newest addition to the trio is Valerie Alcalde Bussey, the force behind Sotol Rarámuri.

She was born in Michoacan, but her father is from Chihuahua and the family moved to Juárez when she was very young. Of the three women, she might have the most background with sotol. Despite its low social acceptance, her father appreciated it culturally and as a beverage. He even made sure his children were familiar with it, especially how strong it is, despite disapproval from mom. For this, Alcalde considers her father her first educator.

Her identity lies in this border town. She was educated on both sides of the border, is fully bilingual, and has a degree in economics from Texas Tech University. After graduating, she began a promising career in the US with Emerson, but pride in her state drew her back to sotol, especially after seeing Navar’s Flor de Desierto. She contacted Navar, who linked her to De León, and in 2018, she began learning from master sotoleros like Kali Álvarez from Guadalupe and Bienvenido Fernández in Madero. Only one year later, she entered a jóven sotol called Remari into Concours Mondial de Bruxelles where it won a medal (Mexico category) in 2020.

Alcalde’s focus has been on her signature brand Ruramari, with an almost exclusive partnership with the very highly regarded Bienvendio Fernández of Madero. This partnership has worked well not just because of Fernández’s expertise and easygoing nature, but also because with three sotol-making daughters of his own (Norma, Aracely, and Viviana), Alcalde feels especially comfortable doing business with him.

Like Navar, she works to make this artisanal product available nationally and internationally, particularly in the United States. And like Navar, she finds it easier to still sell outside of Chihuahua but expects that to change – “…what happens a lot in Mexico… [is that] foreigners come and when they appreciate it, Mexicans begin to appreciate what is [already] ours.”

Fortunately, Rarámuri has been invited to promote her woman-owned sotol brand in the upcoming Mexico in a Bottle event in Nombre de Dios, Durango on June 8th, a unique chance to experience this highly-regarding tasting series outside the United States.

In Mexico, she has concentrated her marketing efforts from Mexico City west toward Guadalajara, likely because of her Michoacán connections. In this region she holds tastings, but still finds it harder to do the same in Chihuahua.

Alcalde did not sell her first bottles of sotol with the aim of starting a company; after all, she already had a corporate career. But success and the chance to positively promote her home state convinced her that this is where her path lies. “[Marketing sotol] is very agreeable work, because it is like falling in love with the soil of Mexico and its plants. With a little alchemy, you make some magical and divine spirits, right? You are tasting this something that is very natural, very special because it is very artisanal and besides it is working with the Mexican soil, right?

Why relationships are key to their sotol success

What struck me about De Leon’s, Navar’s and Alcalde’s stories is although they have their own paths, a common element in their success is putting importance on relationships – something that can be missing in stories of entrepreneurship.

For all three, family played some kind of role as inspiration and/or with practical help. As Chihuahuenses, sotol has played a part in these families’ identities. De León has made 5 Tragos an important part of the family’s ranch activities, and for Navar, it has meant combining her culinary expertise with her brother’s status as a sommelier.

They all quickly learned the importance of building relationships and trust with sotoleros who have had to work clandestinely for generations. And they know it’s not enough to earn that initial trust – those relationships need to be nurtured to continue to thrive.

But perhaps most surprisingly: the three consider their personal and professional relationships with each other as instrumental to their success. They do not see each other as competitors for limited market share, but rather as colleagues, whose efforts and success benefit not only themselves but also the sotoleros they work with and their beloved Ciudad Juárez.

As Alcalde puts it, “We three are such good friends. I have learned much and to be honest, without [their work], it would have been much harder to do this. I feel this sisterhood among us. And it is not just us three, there are now organizations of women in distilled beverages to provide support.”

She refers to efforts to network with other female spirit makers, especially mezcal and those in bacanora just across the border in Sonora.

That support is important as they are women in what has been very strongly a men’s domain – both in the making and the drinking. Machismo here perhaps can be somewhat forgiven because being involved in sotol was pretty dangerous until recently.

But in the past years, sotol has been undergoing a kind of renaissance, bringing in the interest of people outside of isolated mountain and desert committees.

Even so, being a woman can make the job more difficult. Traditional and older sotoleros may not be comfortable doing business with a woman, sending out a wife as an intermediary or just refusing to negotiate at all. But Alcalde states, “I don’t want to go too much into the issues of being a woman because I don’t want to get hung up on making myself some kind of a victim. There are good and bad men just like there are good and bad women.” In addition, there are other factors that can come into play; De León, Navar and Alcalde are also educated city people. Think of a New Yorker venturing in very rural Appalachia to try and do a moonshine deal.

Being the first mover, De León perhaps had it the hardest, noting “My dad always accompanied me, opened paths for me. At the beginning they (the men) were not used to [working with women]. Because of my age, they thought this was just a school assignment, they never thought that I would dare take it this far. I still get “I don’t like doing business with women” but the important thing is to not get discouraged and show that it is possible.” With all now having successful track records, convincing makers and buyers is now significantly easier.

All three have experienced critical and economic success but all realize that there is still much more to be done. Navar and Alcalde have found much greater success building markets for sotol outside of Chihuahua. De León has made sotol and her ranch a kind of tourist attraction in part to convince locals to take that first sip.

I should also note that the three credit traditional sotoleros for the success of their brands. De León applied what she learned in the sotol country of Aldama and adapted it to the Dasylirion varieties of the Juárez desert. Nava and Alcalde depend on the generations of experience of their maestros, only selecting varieties, not looking to change them in any way.

Whatever attitudes might have been in the past, sotoleros realize the importance of getting their product out beyond the desert and mountains. And partly because they are women, working with De León, Navar and Alcalde gives them access to an international audience eager for something new and authentic.

Leave a Comment