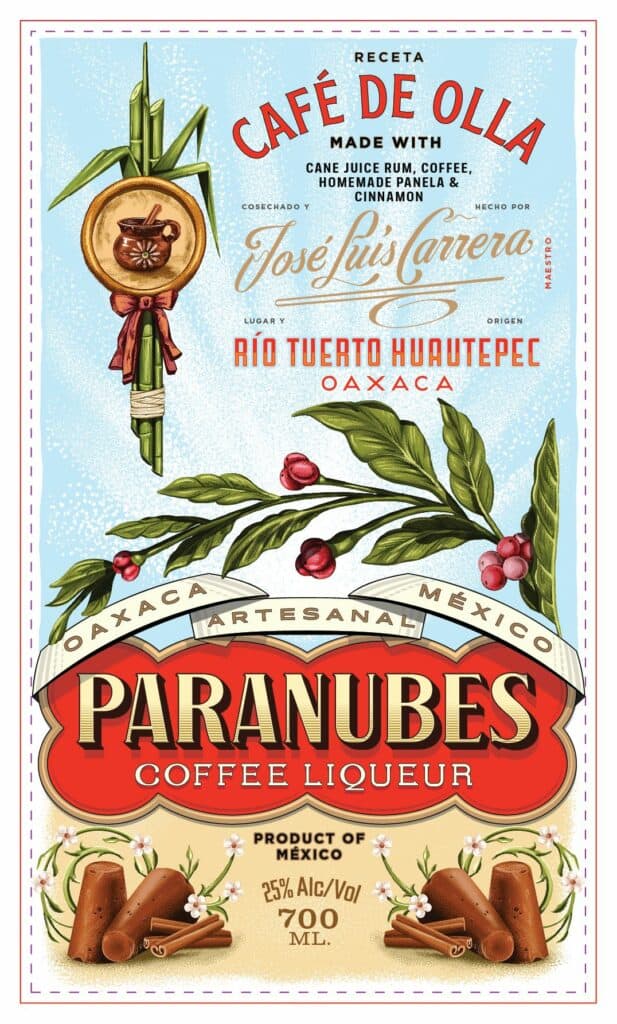

Not in the mood for boozy coffee syrup? Paranubes has your back. A look at their new coffee liqueur and what makes it special.

Can you bottle the essence of a region? After tasting the new coffee liqueur from Paranubus, I’m inclined to think so. This cafe de olla liqueur is as original as its base spirit–the much lauded Paranubes Rum, or aguardiente de caña, as it’s known at its point of origin in the Sierra Mazateca of Oaxaca.

Paranubes Coffee Liqueur is in a class of its own–more akin to an amaro than it is to, say, Kahlua or Mr. Black. The briny yet candied notes of the rum are expertly amplified by spiced coffee.

“It’s very taste the place,” Kami Kenna says of the recipe she formulated for brand owners Judah Kuper, Francisco Terrazas, and Dylan Sloan.

In Mexico, Paranubes Coffee Liqueur is marketed as Paranubes Cafe de Olla. In addition to elevating ingredients from a specific region in Oaxaca, the liqueur celebrates the widespread Mexican tradition of cafe de olla, or coffee steeped and simmered with dark brown sugar and cinnamon. (Some recipes call for additional aromatics.)

Kami wanted to figure out a way to bring that comforting yet layered flavor to a coffee liqueur. She set out to create something totally different from any coffee liqueur on the market.

“Everyone here does a coffee liqueur,” Kami says from her kitchen in Oaxaca. “Because there’s coffee growing everywhere and there’s mezcal everywhere. So usually these liqueurs are mezcal-based and they’re very very literal, in the sense that they take coffee, usually a pretty dark roast, and they macerate it in mezcal and they add sugar and they sell you a coffee liqueur. And some of them are better than others, but it’s just very literal.”

Paranubes Coffee Liqueur stands out in every sense–from production methods to base spirit. Paranubes Rum is made by José Luís Carrera, a third generation producer who grows coffee and four kinds of sugarcane in ancestral fields. In addition to rum, he turns the cane into panela–the hard brown sugar beloved by punch aficionados and abuelas alike. (This is commonly known as piloncillo.)

On rum and rural economic development

José Luís’s distillery is on a river at the bottom of a steep valley. Judah describes the place as “magical” but, on a more practical note, says he thinks the lower altitude is ideal for fermentation, which is likely one reason that José Luís’s rum is so good.

Both Judah and Kami are enamored with the Sierra Mazateca, which is about a day’s drive north from the city of Oaxaca. Kami becomes animated as she describes the journey into the mountains, passing through pulque country and then up to a region that’s totally distinct from the rest of the state.

“There’s no mezcal culture. People are making aguardiente. There’s sugar cane everywhere, it smells different, all the food tastes different, everything is different,” Kami says.

“It’s so rugged the conquistadors never really conquered it,” notes Judah, who was first lured into those mountains when he took a sip from a bottle of distinctive Mazatecan aguardiente.

This was around 2013, and Judah had already founded Vago, a notably successful mezcal brand. But he was intrigued by the rum and began exploring the mountains to visit trapiches—the word for sugar mill that’s also used to describe aguardiente distilleries.

When he first ventured into the Mazateca, he noticed that the distillers saw themselves as sugarcane farmers who were trying to make some extra money. There wasn’t a reverence for the spirit and the producers as there is in mezcal culture. He says the distillers were mostly just selling to the town drunks and they weren’t proud of that. And yet, the spirit itself was exceptional.

He says he visited “about a hundred trapiches” before he met José Luís. “His rum was the best quality that I found, and I just found the guy really interesting. He’s a deeply religious guy, but he was a really beaten down guy at that point. He put three of his kids through college, and they went to the city and they became professionals. His wife had moved to the city as well.”

Judah says José Luís’s family was skeptical of his choice to continue farming and distilling because he wasn’t making any money.

“He was in a really dark place because his whole family had left him and they didn’t respect him,” says Judah. “He just wanted to be a farmer up there and do his thing.”

In addition to bringing an usual new spirit to market, Judah saw Paranubes as a way to create economic opportunities for José Luís and his community.

“The poverty up there is on such another level than it is even in the mezcal world,” says Judah. “Obviously there’s a lot of poverty in the central valley, but it’s just worse up there. It’s farther away; there’s less economy; the living is a little harder.”

His idea was much bigger than just creating a single brand.

“The goal with Paranubes was to bring the first agricole-style rum from Oaxaca. We thought, Let’s create a category where more brands can follow us, and let’s see if we can change the fortunes a little bit in our own little way–in that town and also in the Sierra Norte.”

It worked. He estimates there are now at least eight Oaxacan agricole-style rum brands on the market.

The strategy was successful on the personal level as well. José Luís found respect for his labor and talent.

“One by one, his kids moved back, his wife moved back, he started employing the whole town…to the detriment of his own finances,” Judah says fondly. “He’s been the president of his municipality multiple times, and he just loves being that guy who is the facilitator in his town.”

Experimenting with aromatics for a cafe de olla liqueur

The idea behind Paranubes Coffee Liqueur was to continue supporting economic development in the Mazateca by creating a spirit that would use the coffee José Luís grows, as well his panela and local herbs and spices.

Kami appreciates this goal, but also looks at creativity on an abstract level.

“The coffee liqueur needs to embody that place,” Kami says. “Obviously José Luís’s rum does. But anything that’s a line extension from Paranubes needs to have that essence.”

People are typically part of the essence of a place, a point that’s not lost on Kami. “It needs to have the identity, the thumb print of José Luís,” she says.

To make a cafe de olla liqueur, one ingredient was a no brainer–cinnamon. But that wasn’t enough. Kami wanted to create something layered and complex without obscuring the base spirit.

“This is what I think is so fun, and abstract, and stressful about creating a recipe. You’e aiming for an end product and you want the end product to be cafe de olla. But there’s a million ways to get there,” Kami says.

She’s no stranger to the process. During her award-winning career as a bartender, she developed a deep well of experience in mixing ingredients to find the perfect balance. She also worked on an herbal liqueur during her tenure as assistant distiller at Destilería Andina in Peru. “When you’re making something on a larger scale you have to think about things differently,” she notes. “I liked that work. It’s a lot of documentation, it’s a lot tasting, it’s a lot of trying everything and seeing what sticks, essentially. And it’s something I want to keep doing for sure.”

Her eyes gleam–she’s giving off a mad scientist vibe.

“My idea isn’t strictly I’m making a cafe de olla. It’s also, What do I want to make next? So I have an entire library of macerations and sometimes it’s like, Is this herb going to be better fresh? Is it going to be better dried? Is it going to be better toasted on the comal? How does the plant need to be treated first?”

This results in ongoing experimentation.

“There’s a bunch of old growth elder flower trees here in Oaxaca and they only bloom for a few nights,” she recalls. “So I went out and harvested and was like, let’s play with that!”

The elder flowers didn’t make the cut for the cafe de olla. Instead, Kami zeroed in on chilhuacle, sourced from the same region as the rum–La Cañada.

“It’s a black chile, and it’s the most expensive chile,” she says and laughs. “It’s used often for mole negro here. Chilhuacle is a quintessential chile, and it has a lot of those toasty, roasty notes that you get from roasted coffee. So that is a good background for the coffee–it supports that flavor.”

Putting the coffee back in coffee liqueur

Kami is serious about coffee.

“I prefer really good coffee. I worked with coffee in Peru, and then, preparing for this, I took a coffee course and really studied coffee,” she says. Many people encouraged her to use extracts to formulate the liqueur but she wasn’t having it. She describes the process of working with Francisco Terrazas on the formula.

“We make a big concentrated batch of cold brew that we proof the spirit down with,” she says. “There isn’t any maceration of the coffee into the spirit. Everything you’re getting is a carefully metered cold brew that we worked on for a long time to figure out the exact time, the exact grind, the exact roast, and the exact quantity with the water.”

Finding a new formula

It has been a process of trial and error, but some of the “error” has been outside of Kami’s realm of control. After launching in Mexico, they were planned to distribute the liqueur in the US, only to discover that avocado leaf and another botanical were not FDA approved. It was back to the drawing board for Kami.

“Avocado leaf is an emulsifier, so I had to think, What is something that can be used in its place that’s also aromatic and really flavorful? So that’s where I started.” Her friend Matt Spinozzi (a fellow beverage formulator and consultant) suggested zarzaparilla (sarsaparilla). It hit.

Kami is pleased with the new formulation. “Sasparilla is the emulsifier, which also serves as a deep background canvas for the coffee, and the cinnamon, to bring it all together,” she explains. Paranubes Coffee Liqueur should be available in the US in August of 2025.

Judah is quick to sing praises for this iteration, which he describes as more coffee-forward than the original recipe.

“I drink it neat,” he says. “I pour it on top of whiskey. It’s so good on top of whiskey that I don’t even bother to make a cocktail. It’s really good with tonic water on ice–it’s delicious.”

He’s pleased with the spirit on every level.

“I think it’s the coolest label I’ve ever seen,” he says of the artwork by Abraham Lule, a Mexican graphic designer who lives in Brooklyn.

“He is the best package designer in the world. I truly think so. He’s a great designer, and he’s an incredible typographer, which I think is overlooked when you’re talking about design. His ability to mix fonts that shouldn’t mix—people don’t realize the nuance of that type of stuff unless you’re really in the design world.”

Lule worked on the Vago redesign, but Judah notes there were a lot of people in the room for that one. For his own project, he wanted to see what Lule would do if given free rein.

And ultimately, that’s why Paranubes Coffee Liqueur is so good on every level. Judah and his partners have found the right creators and respectfully given them space to play. The end result is a spirit that shines.

This sounds amazing! Can I buy it in New Orleans?

It will be released in August. Not sure about which markets but ask at any liquor store that sells Paranubes and ask them to order it!

Can’t wait to try it! Label is stunning!

what a great story, I can’t wait to try, Oaxacan Agricole is really fun product, this should be even more so

Hi Cree! I hear the release is going to be pretty extensive in terms of states, so I’m assuming it will be available in New Orleans later this summer or fall. But you would probably have to go to a specialty liquor store.