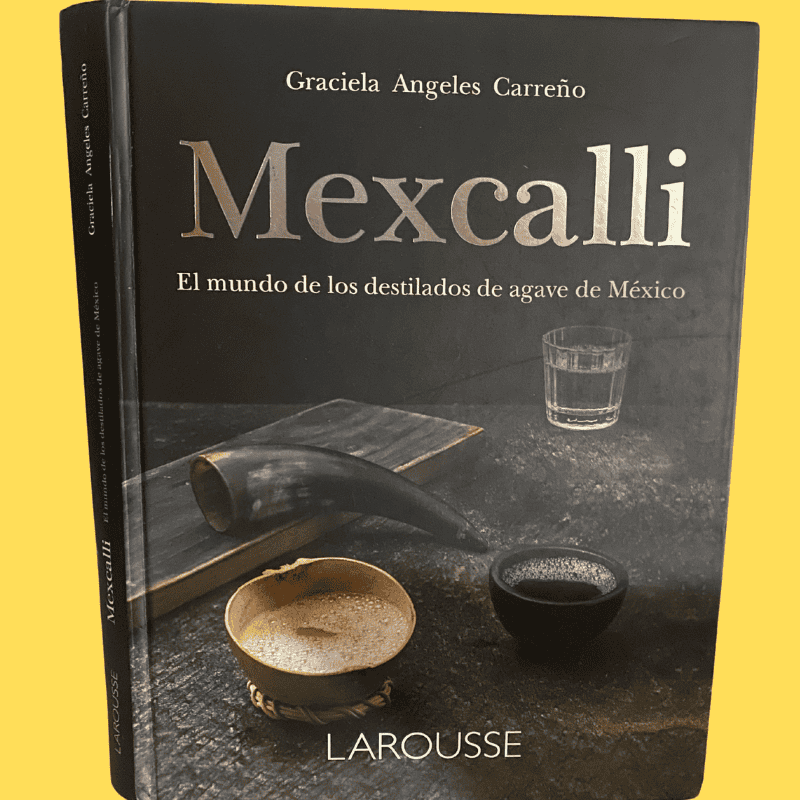

In an age when so much information about agave spirits is gleaned through social media videos, cocktail photos, tasting notes, and curated images of agave fields, reaching for a book might feel a bit arcane. But agave spirits demand depth—an understanding of who makes them, how they’re made, and why they matter. Mexcalli is that book.

Written by Graciela Ángeles Carreño and edited by Larousse, Mexcalli is not your standard spirits guide. It is a book that doesn’t chase trends but instead, it traces roots. With a voice that blends lived experience and academic insight, Graciela gives readers an honest, reflective, and at times critical view of what it means to produce agave spirits in Mexico today. This is the story of mezcal and other agave spirits told from the inside out.

Graciela Ángeles Carreño is a fourth-generation mezcalillera from Santa Catarina Minas, Oaxaca. Since 2008, she has led Mezcal de los Ángeles alongside her family. With a background in communications, a master’s in sociology, and a PhD in rural development, she carries both the tools of research and the perspective of lived tradition. She is also the founder of Proyecto LAM and Biblioteca El Rosario, two community projects that deepen her commitment to education, culture, and land.

“I could say that everything I’ve lived has nourished this book. It draws from over twenty years of experience in the production, commercialization, and analysis of what has unfolded in the world of agave spirits in Mexico,” she told me in a recent interview.

At first glance, Mexcalli might appear to be a reference manual: organized, encyclopedic, filled with terms, illustrations and technical clarity. But a few pages in, it becomes something else. It reveals itself as a narrative about connection—to land, to language, to process, to people. It’s a story of how agave spirits are made in a community.

Each chapter of Mexcalli unfolds with purpose. Graciela begins with origins: not just of the plant, but of human relationships with agave. Mexico is home to 159 of the 211 agave species known in the Americas. These plants have co-evolved with humans for over 10,000 years, offering food, fiber, shelter, and drink. That history matters. As she writes, “I wanted to give voice to the communities few people know about—those who also make agave spirits. I was especially interested in recognizing the diversity of processes, agaves, and language.”

Where the book truly distinguishes itself is in the chapter devoted to the production process—not because it offers a step-by-step manual (plenty of books do), but because it unpacks how each method has come to be. From agave maturity and harvest timing, to roasting methods, fermentation practices, and distillation, Graciela outlines each step not as a fixed formula, but as a dynamic tradition grounded in place.What makes this section so compelling is how it reveals that a specific process is not always a matter of personal preference—it can be dictated by local tradition, the outcome of years of trial and error, or sometimes, simple coincidence.

Why use a particular kind of wood? Why does the same still function differently in Oaxaca versus Estado de México? These choices are shaped by environmental conditions, biodiversity, cultural memory, and generational knowledge. This is especially true for distillates made through traditional, campesino methods—less industrialized, more intuitive—where flavor and aroma are richer, more complex, and unmistakably tied to the land and people who shape them. Even the yeast, often an afterthought in many texts, becomes a central character here, carrying the unique signature of its environment.

This chapter does more than explain a process—it reveals a cosmovision or worldview; one where adaptation, evolution, and care for the environment are central. For example, she notes how in Michoacán, encino (oak) is preferred, while in Jalisco it might be mezquite or huamuche also known as guamuchil. It’s a reminder that mezcal isn’t just regional—it is actually hyperlocal.

“Mexcalli seeks to speak of diversity: to honor the names communities give their spirits, and the cultural contexts in which these drinks are produced and reproduced,” Graciela told me. That diversity is in the stills, the language, the recipes, and the unspoken knowledge passed down over time.

She also addresses contemporary tensions: the debate over the origins of distillation, the ritual behind mezcal de pechuga, and the rise of mezcal produced outside Mexico. She even dives into the contentious conversation around the Denominacion de Origin (DO). She outlines not only what the DO is, but what it excludes. Her critique is clear-eyed and backed with examples like Zapotitlán de Vadillo and Aguascalientes. She discusses how the current legal structure can distort traditional practice, encourage monoculture, and marginalize long standing producers. Still, her tone is constructive.

In each case, Graciela offers perspective without dogma. She acknowledges innovation but pushes for respectful engagement with origin communities. If you want to be part of the industry, she seems to say, you better get to know the context.

Mexcalli manages to be both accessible and rigorous. It’s not romanticized, but it is reverent. For bartenders, buyers, drinkers, and researchers alike, this is a book that offers context where there’s usually noise. A bottle of mezcal might tell you where it’s from. Mexcalli tells you why it matters. This is especially clear in the chapter on tasting, where Graciela pushes back against imported European models—like wine-based flavor wheels—and advocates for frameworks rooted in the gusto histórico of each community. She suggests that the people who make the spirits should also shape the language used to describe them. It’s a bold but necessary stance, affirming that taste is cultural and sensory memory is local. Tasting mezcal, then, is not just about what’s in the glass—it’s about who made it, and how their environment and tradition inform every note.

As for me, I read the book with a bottle of Marteño close by, flipping through past notes from interviews with Graciela and filling the margins with fresh thoughts. I’d recommend Mexcalli to anyone who wants to make more informed choices about what they drink, and why. And to those already immersed in the agave world, it offers something increasingly rare: perspective grounded in land, community, and time.

Because mezcal was mezcal long before it was a brand. And thanks to voices like Graciela’s, it still can be.The book is in Spanish and is currently only available for purchase in Mexico through Amazon, El Librero, and at Real Minero tasting room in CDMX.

References

1.The word Mexcalli comes from the Nahuatl language and is composed of metl (agave) and ixcalli (cooked), meaning “cooked agave.” It is the linguistic root of the word “mezcal.” By choosing this title, Graciela emphasizes the ancestral origin of the spirit and the continuity of indigenous knowledge systems that still define its production today.

2. Graciela prefers the term mezcalillera over maestra mezcalera to emphasize her role as a working producer grounded in practice rather than elevated through branding. As she explains in her essay in Miradas Femeninas del Mezcal, the figure of the mezcalero or mezcalera has often been shaped like a myth or star persona—at times rustic, at others refined, sometimes even shamanic. These attributes are often projected by consumers or cultural promoters rather than rooted in reality. In contrast, mezcalillera highlights her connection to the labor, land, and lived process, not the constructed image.

Looking forward to the English translation! She will be at Mezcal por Siempre agave festival in Los Angeles on 9/12 signing copies.

Likewise for our Mexico in a Bottle event in San Francisco!

Buenas tardes Maestra Graciela.

La felicito por su libro Mezcalli está muy completo y didáctico y con una estética muy cuidada.

Somos apasionados del mezcal y promotores del mismo en la CDMX, en nuestro camino hemos notado que por lo menos aquí falta mucha información que permita al consumidor apreciar las características organolepticas del mezcal con su contexto cultural, social y como hilo conector y soporte económico de comunidades mezcaleras.

Nosotros nos apoyamos en su obra para guiarnos y difundir esta idea.