At a time when mezcal is seeing a shift toward commercial practices, traditional celebrations and rituals help unite producers in Oaxaca. Contributor Anna Bruce reports.

Toward the end of July, Oaxacan pueblos are bursting with fiestas and other traditional celebrations. These daily events include mezcal fairs and saints’ days. Fiestas patronales, which celebrate patron saints, are major events in Oaxacan towns and villages. Mezcal is a central part of these celebrations; copitas are shared during processions and festivities, fuelling social connection and community pride.

This year, I attended the saint’s day celebrations for Santiago de Apóstol, the patron saint of the mezcal-producing community of Santiago de Matatlán. Founded in 1575, Matatlán is a Zapotec town in Oaxaca’s Central Valley, about an hour from Oaxaca City. Arriving in the town, you pass under a welcome sign that proudly declares it the “Mezcal Capital of the World.”

Mezcal is integral to the way of life here, with generations of producers perfecting artesanal distillation in family-run palenques. Most of the artesanal mezcal making its way out of Mexico comes from this town, where hundreds of distilleries produce the spirit. We’ve also been seeing significant local growth in commercial mezcal production to support recent demand for cocktail mezcal in the international market. The globalized interest in mezcal is reflected in the growth of the town’s economy, as well as return migration from the US.

In Matatlán, Zapotec and Spanish traditions are intertwined, resulting in a unique cultural blend. While the Spanish brought major changes, imposing the Latin alphabet, a patriarchal European structure, and Christianity, Zapotec people have maintained many core traditions, often adapting them to new contexts. Matatlán’s Ta Guiil Rei’ñ” Community Museum showcases local culture, mezcal production, and pre-Hispanic artefacts. Here you can learn about how the Zapotec and Catholic histories are interwoven through time.

The interaction between Zapotec and Spanish cultures is vividly expressed through Oaxacan festivities. Many Zapotec celebrations incorporate Spanish customs, resulting in unique events that reflect the complexities of their cultural identity. Examples of this include Guelaguetza, Dia de Los Muertos, and the October 7 feast of the Virgin del Rosario, which overlaps with the pre-Hispanic Zapotec procession, yaal zaa, the presentation of the harvest at the end of the rainy season.

The name “Matatlán” is of Nahuatl origin, meaning “place of nets,” possibly referring to fishermen’s nets made from the fibers of ancient agave used to fish a mythical lake.

In Un Viaje al Mezcal, Entre Historias y Tradiciones (2025), mezcalero Israel Perez Santiago explores how mezcal has developed against a backdrop of Matatlán culture. He writes: “We remember that thousands of years ago, our ancestors said that there was a huge lake in the central valleys of Oaxaca.” Santiago was added to Matatlán in honour of the patron saint, Santiago Apóstol. Santiago Apóstol (Saint James the Apostle) is known by many names, including James, son of Zebedee, Saint James the Great, or Saint James the Elder. “Santiago” is a Spanish derivative.

The saint is often portrayed as a warrior on a white horse, a matamoro fighting for Christianity. He is also depicted as a pilgrim carrying a staff, purse, gourd, hat, and, most notably, the scallop shell, his emblem. Some may recognise this symbol from the Santiago pilgrimage in northern Spain.

In the state of Oaxaca, it is the mayodormos and their families who are responsible for managing a towns’ saints day celebrations. The role of mayodormo is a significant religious and social practice, where individuals or families take on the responsibility of organising and financing religious festivals. To become a mayordomo, one must assume a series of positions over many years, progressing within a political-religious structure.

The position now includes both male and female figures. According to Israel, “The role of the mayordomo of Santiago Apóstol has been adapted to the new generation, presenting not only the religious faith but also folklore. The mayordomo now not only represents the male figure but also the female mayordoma as his great companion, representing family unity.”

Crucially, the tradition has survived through various historical periods (institutionalised church, Independence, Reform Laws, Revolution) because communities appropriated the role, transforming it into a symbol of cultural resistance and spiritual sustenance. It can be viewed as a mechanism for wealth redistribution within communities and among individuals.

Mezcal is part of the religious services. Israel explains, “The church authorities and mayordomos invite magueyeros (agave farmers) and mezcaleros to participate in a special mass, where they offer their mezcals and magueyitos.”

Mayordomos serve for a year, beginning each November. Duties include keeping fresh flowers in saints’ vases and attending daily events. They are responsible for covering significant expenses, including musicians, dancers, decorations, candles, incense, and fireworks during celebrations. From a religious perspective, their service is believed to prevent the wrath of the patronal saint.

Local stories of the saints imply certain precocious traits: the statue of Catalina, patron saint of Quiane is said to have been caught sneaking out of the church in disdain when not given sufficient reverence. In the case of Santiago Apóstol, legend states that the saint himself chose Matatlán as his town. However, he stayed away until the work on the church was satisfactory.

In Santiago de Matatlán, there are 20 mayodormos, who share responsibilities throughout the year. Then there is the mayodormo grande, who is specifically responsible for the patron saint.

This year, my good friend mezcalero Jose Santiago Lopez, has the position of mayordomo grande in the “mezcal capital.” He put himself forward for this role and was subsequently elected. It is a great honor for him and his family, but it is also a huge amount of work year-round, managing upkeep in the church and community celebrations, so he hasn’t been producing much mezcal!

Jose invited Brooks and me to attend a series of events, which began on May first and continued until the first of August, with numerous religious services, fiestas, and parades in between.

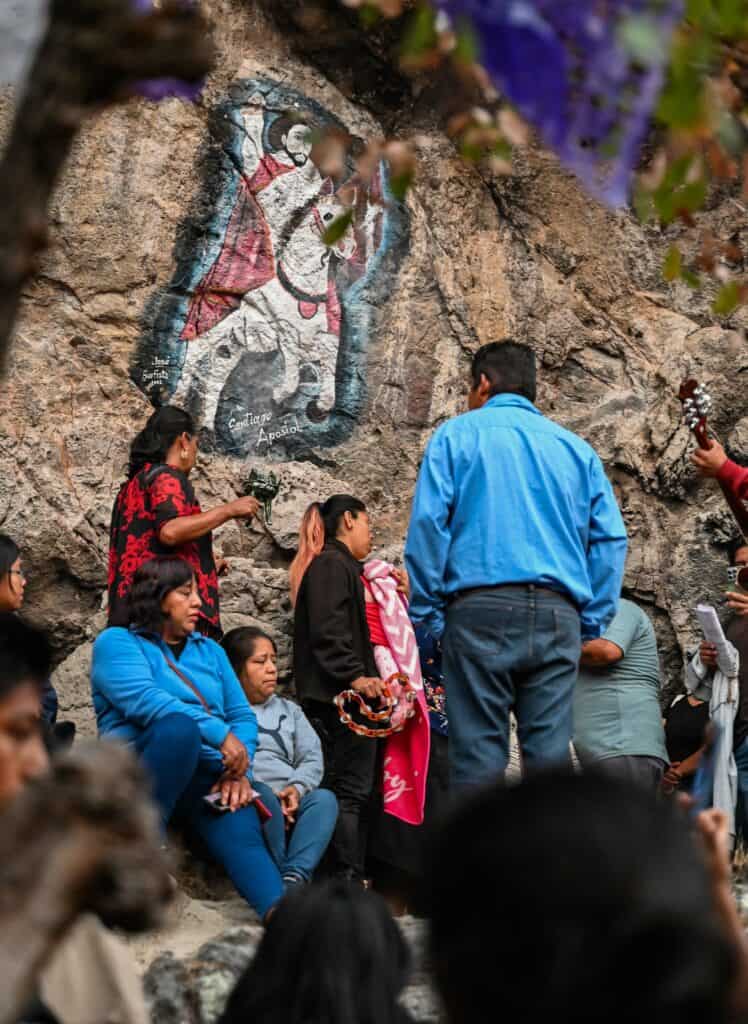

Ahead of the initial event, we camped on the roof of Jose’s palenque, to be up at 4:30 AM to begin the walk into the hills behind Matatlán. Joined by a procession from the community, we wound our way along a steep path, arriving at a cliff-backed ledge in time for dawn.

As the sun came up, Jose gave a sermon in Zapotec, followed by singing, and of course, a celebratory mezcal. As we cheered the sunrise, a large painting of Santiago Apóstol began to catch the light on the cliffs behind us. After this spectacular moment in the mountains, the crowd made their way back toward a plateau below. Here we shared in tamales and horchata, while fireworks exploded nearby!

Leading up to the patron saint’s official day, there are nine novenarios (daily masses) funded by the mayordomo. After each Mass, the mayordomo’s family shares food, beer, mezcal, and treats with attendees. On July 24th, the fiesta officially starts with a traditional calenda (evening procession) featuring live banda, dancing, and sharing of beer and mezcal along the route. The same night includes the Quema de Castillo, which is an enormous tower made from carrizo (reeds) and filled with fireworks.

July 25th is the main mass honouring the saint, followed by a procession carrying a statue of Santiago on horseback through the streets of Matatlán. The crowd stops at each corner for prayers and singing before making their way to the home of the mayodromo for food and music.

Israel remembers the experience of this procession in his book: “We see the women arriving, dressed in their traditional costume called enredo, which is a one-piece blanket of purple painted with cochineal, an embroidered huipil, and a black silk shawl. On their feet are butterfly sandals, and on their heads are braids with red ribbon and 24-karat gold bell earrings. On their heads they carry very large and beautiful flower baskets. The sounds of the wind band are heard joyfully, and the men, with a bottle of mezcal, offer it to the visitors.”

At Jose’s palenque, he had filled in his horno to make space for the band alongside the chairs and tables that were packed into the space. After food, tables were cleared to make room for strings of pomegranates and lime. While we helped make these into garlands, I got to know Jose’s nephew, Erik Mateo Mateo. Erik recently moved to Matatlán from LA. He currently works as a magueyero and has aspirations of making his own mezcal.

Despite growing up in the US, Erik explains that his community, “Tries to do the most to keep it as traditional as possible. I’ve grown up always surrounded by the traditions and the culture of Matatlán.” In 2009, he and his family spent a year in Matatlán so that his father could carry out the role of maydormo grande. He said that helping his uncle Jose was a “breeze,” because he already knew the rituals and traditions required to carry out the role.

Erik considers that the vast majority of the traditions have pre-Hispanic influences. “Zapoteco still has an enormous influence–all the adults speak it as a first language,” he says. “Inside the altar it is spoken as a sign of respect, then it is followed by Spanish for anyone young who doesn’t fully understand.”

In the early 2000s, many young adults migrated to the US with the aim of providing for their families back in Matatlán. “Today, the population in Matatlán is growing,” Erick says. “With the boom of demand in mezcal, the economy here in Matatlán is rising every year. Hence, the population that immigrated out of the pueblo to the US has started to move back to Matatlán. The traditions haven’t been lost or forgotten.”

Erik plans to stay in Matatlán to pursue his goal of becoming a mezcalero, and he’s already working toward the role of mayordormo. He explains that more people are volunteering to do their tequio, a historic practice of community service: “Like myself,” he says. “I got married here in Matatlán in 2023. And I offered to do my first service as panteónero. Now I’ll be climbing the ladder of services.” (Panteónero refers to a person who works in a cemetery. They perform various tasks such as cleaning, surveillance, or assisting families during burials.)

Erik went on: “In Matatlán, mezcal is part of our identity. When we celebrate something, we share mezcal. For my wedding, the day we went to pay the butcher who killed, cleaned, and served the toro, he gave everyone a copita de mezcal. This was to celebrate that everything went well and the compromiso was successful. He was responsible for over 400 servings of food. It is a ritual.”

As Erik and I finished making our fruity garlands, a young bull was brought into the palenque. He was adorned with our handiwork to be presented to the leaders of the municipality at a jaripeo (rodeo) later that evening. As mayordomo grande, Jose and his family are invited to the jaripeo as VIP guests.

This year the jaripeo was hosted alongside the new venue for Matatlán’s feria de mezcal. The feria was housed in a large tent with a stage, pony rides out front, and a showcase of classic trucks out back.

Over the years as I have been based in Oaxaca, the mezcal fairs and Guelaguetza celebrations have grown and shifted in their character. As exciting as it may be to see the ferias move to bigger venues, they have taken on a sense of the circus. A criticism this year has been that the fairs are leaning more toward brands selling cocktails, rather than being a platform to share traditional knowledge and artisanal mezcals. This was evident at the massive mezcal fair in Oaxaca City, which packed the convention center for almost two weeks. At the Matatlán feria, there were a couple of brands like RosaLuna making cocktails, but it was predominantly a collection of local producers catching up over their range of mezcals (and their trucks).

Israel considers events like the feria as having their place in Matatlán. He writes: “Mezcal fairs, the heaviest piña contest, and the classic mezcal truck parade have been key elements of the promotion and presentation to visitors, who take home the essence of Matatlán in a bottle of mezcal.”

A week after the Dia de Santiago de Apóstol, and the conclusion of the feria de mezcal, mayordomo José Santiago López and family returned to the church to redress the saint’s altar as part of the octava ceremony. After the religious element of the day, traditional games were held in the center of town. This is reminiscent of a village fete.

One of the most famous games is called “palo encebado,” which is a 15-foot upright pole greased with oil, with gifts tied up at the top. Whoever can reach the prizes takes them home. There is also a greased pig where the same rule applies…whoever can catch the pig gets to keep it.

Saint’s days in Oaxaca are a time for community, celebration, and the reaffirmation of cultural identity, with mezcal playing a vital role in these festivities. Both the saints’ days and the mezcal fair bring people together in Matatlán. They offer fun and fascination while engaging core values from the community. Erik says, “There is no clash. They are their own thing. The mezcal festival has been growing and becoming its own separate entity.”

Growth in the mezcal market has spurred an expansion of the ferias. This growth also guides generations of mezcaleros’ sons and daughters back to places like Matatlán, engaging a deeper interest in their roots both in mezcal and community practices. For today’s mezcaleros, such as Israel, and tomorrow’s mezcaleros like Erik, there is a place for both new and old traditions, reverence and fiesta.

Leave a Comment