For centuries, alcohol and medicinal plants have shared a role in preservation—of both physical remedies and cultural knowledge. In that spirit, Andrés Isunza and Heráclito López founded Taller Astrafilia over a decade ago as a space to explore the richness of Mexican botanicals through distillation. While the original aim of the Mexico City-based project was to spotlight native ingredients, the team quickly realized that achieving this would require deep collaboration with rural communities, foragers, and agroecological producers across the country.

From this network grew the city’s first microdistillery, guided by a clear intention: to distill with care, from the source. In 2018, Astrafilia became a cooperative, and Ingrid Solís joined the team. That same year, they launched Las Espirituosas, the commercial arm that curates and distributes a full portfolio of Mexican spirits—including Astrafilia’s own line as well as bacanora, raicilla, mezcal, sotol, charanda, and fruit liqueurs crafted by other independent producers throughout Mexico.

I met Andrés and Ingrid at Barra México in 2023. Back then, their project already felt special—but seeing how much visibility they’ve gained in less than two years has been inspiring. In a country where spirits are almost entirely centered around agave, they’re opening a different kind of conversation—one rooted in biodiversity, agroecology, and rural knowledge.

Questioning the system we live in is never easy—especially in such a structured industry like spirits. That’s why I believe telling Astrafilia’s story matters: they’re defying the rules of how spirits are made, distributed, and consumed in Mexico.

What is agroecology? (And why it matters here)

Agroecology isn’t just a method of farming—it’s a philosophy rooted in ecological justice, community resilience, and food sovereignty. It challenges the industrial model of agriculture by rejecting synthetic inputs and monocultures, and instead values biodiversity, local knowledge, and the regeneration of living soils.

It is also a framework for human rights: the right to healthy food, a balanced environment, and the sovereignty of Indigenous and campesino communities over their seeds, territories, and ways of life.

Unlike conventional agriculture—which produces food at industrial scale for mass consumption, often relying on synthetic inputs and sacrificing flavor, diversity, and ecological health—agroecology embraces campesino and Indigenous farming as a way of life.

There is no federal data tracking how much of Mexico’s production is agroecological or organic. That invisibility only underscores how vital it is to protect and uplift models like Astrafilia’s—projects that not only work with nature, but help preserve the livelihoods, foodways, and identities of rural Mexico.

Purpose over production

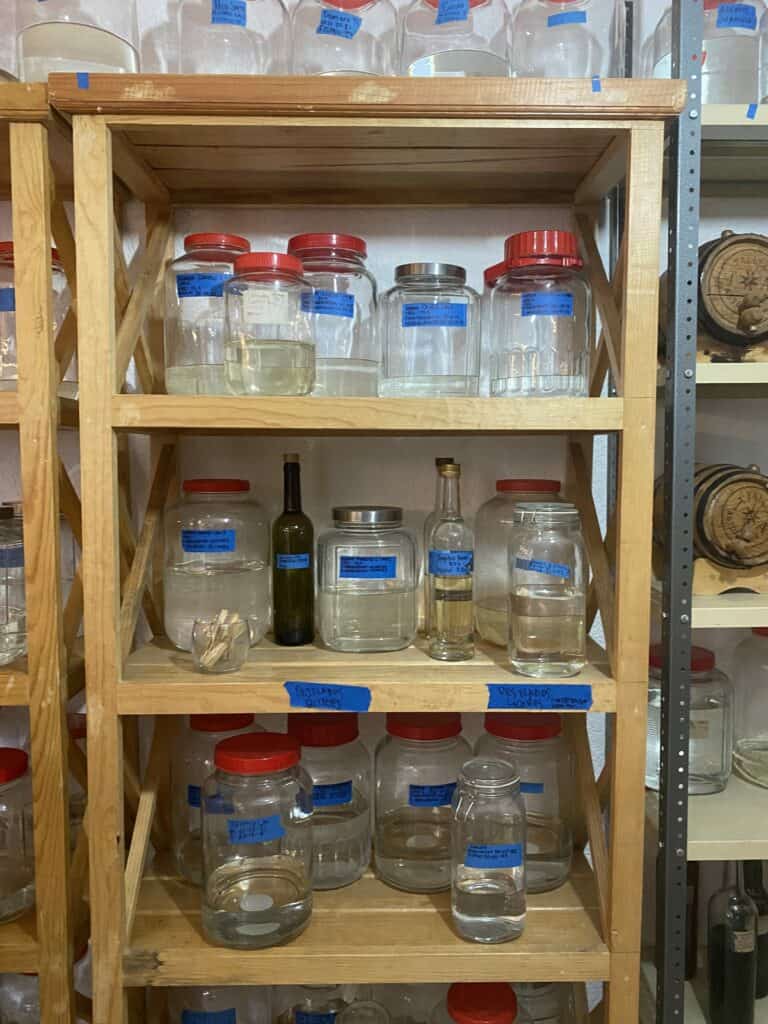

Astrafilia’s flagship spirit is their gin line, Granicera, and their series of botanical liqueurs under the brand Maleza. Every product is handcrafted: botanicals are macerated in agave nectar and sugar-based alcohols, distilled in copper stills, and bottled manually. Preparing 500 bottles can take up to a week.

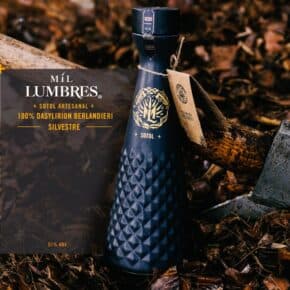

Instead of pursuing industrial-scale production, Astrafilia has focused on growing with intention. In 2023, they reported producing about 800 liters per quarter across their gins, liqueurs, and bitters. By 2025, the project has evolved significantly. They moved into a new distillery with improved infrastructure and systems—still small-scale and artisanal, but more efficient. This shift allowed them to launch new creations, including Tejate, a liqueur inspired by the traditional Oaxacan drink made from cacao, maize, mamey seed, and rosita de cacao (which traditionally beaten by hand until it foams); Bosque, a forest-inspired spirit in collaboration with Rayo bar; and their first mead or hidromiel produced in-house. They also partnered with sotol producer Lupe López (Chupaflores) to release a limited edition sotol.

Production now averages about 750 liters per month or 2250 liters per quarter. Their strongest market is still Mexico, particularly Mexico City, but exports have gained ground. Most of their gins, liqueurs, and bitters are shipped to the United States through Back Alley Imports, where demand for the liqueurs has grown significantly. They also export to Europe—initially just the liqueurs, but they recently began sending bitters too. In Canada, their tonic syrup and bitters have found a niche.

Mexican herbalism and the role of women

Mexico ranks second globally in medicinal plant diversity. Over 4,500 species are used in traditional healing—and much of this knowledge has been carried by women: curanderas, midwives, foragers, and cooks. These women are not only healers, but also ecological stewards and intergenerational knowledge holders.

Yet their role has often gone unrecognized. As researcher Pilar Alberti Manzanares notes, the cultivation and use of medicinal plants has historically been treated as a domestic task—unpaid, undervalued, and excluded from formal knowledge systems. “This lack of recognition,” she writes, “has rendered women’s contributions invisible, despite the fact that their work has improved the quality of life in rural households, contributed to scientific and medical knowledge, and aided in the conservation of natural resources.”

This is why Astrafilia’s collaborations with herbalists like chef Lily Martínez are not just transactions—they are acts of revalorization. In a time when wellness markets in the Global North turn to the Global South in search of “natural remedies,” the risk of appropriation without reciprocity is real.

Chef Lily Martínez, based in Zacapoaxtla, Puebla, grows and harvests herbs ethically. Martinez comes from a family of healers, cooks, and campesinas. She studied agroecology, worked in fine dining kitchens in Mexico City, and eventually returned home to cook seasonally using ancestral knowledge and medicinal plants through her own project called Ixpaktli.

What Astrafilia makes visible is not just a different way of producing spirits—it’s a way that has always existed, even if often overlooked. Every Wednesday, in the local día de plaza in Zacapoaxtla, women from the Sierra and the drylands—many of them Nahua and Totonaca—come down to the town’s market to sell or exchange their goods. Trueque, the ancient practice of barter, is still very much alive. This is where Lily sources many of the herbs and seeds she sells to Astrafilia.

She works with five women who live in different parts of the region—many are single mothers or caretakers. “One of the hardest parts,” Lily says, “is collecting little by little. You have to cut the plants correctly or they dry out. And teaching people the value of their work is slow, but necessary.”

She draws on her family network—four aunts who are cooks and grow their own herbs in their backyards, and a mix of wild terrain harvesting—to build a supply chain rooted in care. “I’ve seen so many women who bring beautiful products to the local market, but don’t always know how valuable their knowledge is,” she tells me. Her dream is to create a community collection center, one that could improve quality of life in the region without forcing anyone to leave it. “The city could never offer what the land gives us here.”

Now, Lily is working closely with Ingrid and the Astrafilia team on a new project: Yolixpa—a macerated spirit made with medicinal herbs and aguardiente de piloncillo. It features myrtle and teasel, plants long used in traditional healing practices for spiritual ailments. “It’s about returning to the plants we’ve forgotten,” says Lily. The result is more than a product—it’s a reconnection, a memory distilled.

More than a brand, a network

In a system that rewards scale and constant availability, Astrafilia follows a different logic. Here, not scaling isn’t a lack of ambition—it’s a form of resistance. You can’t force nature, nor the pace of ancestral knowledge or wild plant harvesting. In this model, scarcity is part of the message, not a flaw. Seasonality is their main value.

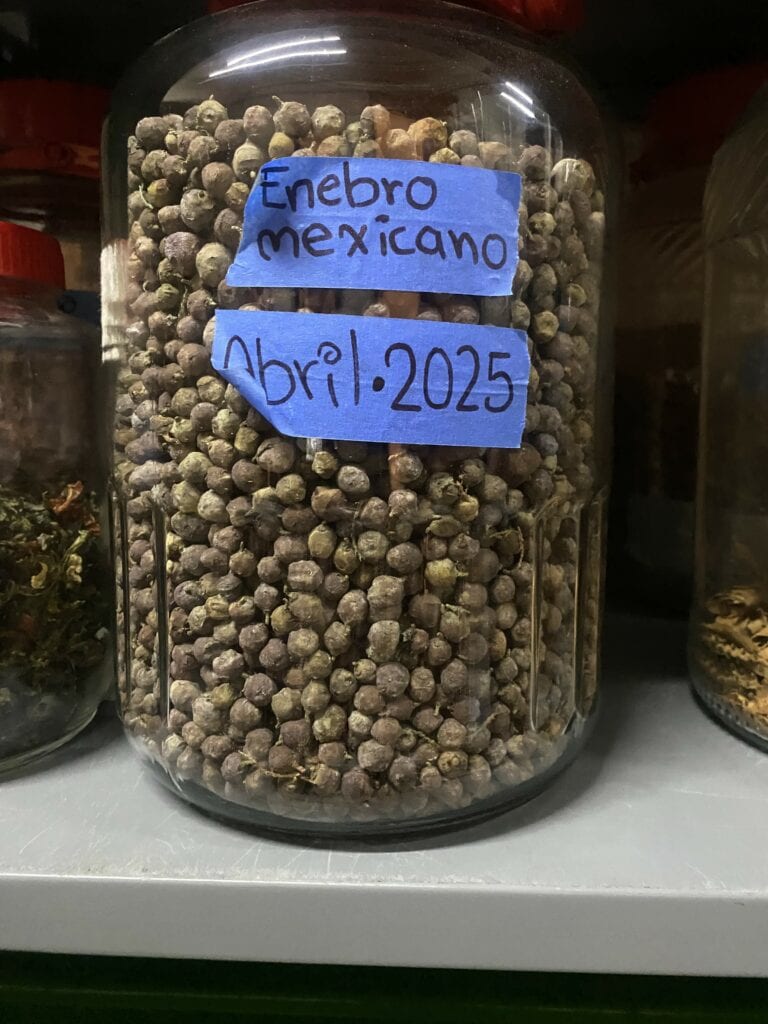

Instead of filling shelves, Astrafilia fills stories: with bartender collaborations, editorial partnerships, and a community that understands that if there’s none left, that’s part of the magic. Each March, they honor International Women’s Day with the release of Ita, a limited-edition spirit whose proceeds support organizations that help women in vulnerable conditions. Each year, they create a new recipe. For example, the last edition was made with bougainvillea, lemon balm, damiana, lavender, chamomile, lime and orange peel, and juniper. They raised 60,000 pesos and donated it to Fundación Barrio Unido.

Astrafilia’s work is possible thanks to a network of makers and producers that includes seven farming families from communities in Puebla, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Estado de México. “We reinvest our profits and keep learning,” says Ingrid. “Some products take one or two years before they’re ready. Our bottling setup is homemade and efficient. We wouldn’t bring someone in just for money—they’d have to bring something deeper.”

That ethos guides everything: from slow R&D to limited editions that reflect not only flavor, but time, intention, and deep-rooted collaboration.

Astrafilia offers a different way to build value—one that doesn’t require losing your soul. If more people understood that the future of good drinking lies in traceability, biodiversity, and local collaboration—not mass expansion—then projects like this wouldn’t be the exception. But that also requires a system that clears the path with better infrastructure, supportive policies, and more equitable access to markets. A system where small producers could thrive without having to sacrifice their values.

Limits that make the model honest

Working with nature means embracing unpredictability. While some of Astrafilia’s ingredients are certified organic, the foundation of their sourcing is not certification—but trust. They know their producers, and they know the processes. But that doesn’t make things easier.

Because batches are small and ingredient use is tightly monitored, a change in climate can ripple through the entire production cycle. This year, for instance, excessive humidity ruined a stockpile of citrus peels they had carefully prepared. They had to discard it. “We try to keep track of exactly how much is being sold so we know how much plant material we’re using,” says Ingrid. “But sometimes you just have to improvise.”

Improvisation in a system this delicate isn’t about cutting corners—it’s about respecting the limits of seasonality and ecosystems. And that’s where customer awareness becomes essential. Astrafilia believes that for these kinds of projects to survive, consumers must ask for products by name. “When you say I want this liqueur, you’re not just buying a drink—you’re protecting a whole production chain,” Ingrid explains. Many of the foragers and producers they work with rely on this income to support their families. Naming the product is a form of recognition.

There’s a future beyond agave

While agave remains the star of Mexican spirits, Astrafilia reminds us that Mexico’s biodiversity holds beautiful possibilities. Their liquors celebrate botanicals like pericón, sesame, cacao flower, Mexican juniper and hoja santa. But how can a project like this scale without losing its soul? The truth is—it can’t. Not in the conventional sense. Its strength lies precisely in its limits: in honoring seasonality, traceability, and the pace of nature.

For Astrafilia, refusing to scale is not a limitation—it’s a form of resistance. Instead of chasing mass production or entering large retail chains, they choose to grow through a decentralized network: strengthening relationships with small producers who grow sustainably; building trust with conscious consumers; and collaborating with bartenders and bars that believe in their story.

Agroecology itself becomes a natural boundary. You simply cannot multiply volume without compromising traceability, biodiversity, and the soul of what you’re distilling.

Ultimately, Astrafilia is building community, not just clientele. If international drinkers understand that the worth of a spirit lies not in always having it on the shelf, but in knowing where it comes from, how it was made, and who made it—then the need for scale dissolves. If there’s none left, that’s part of the magic. If it’s seasonal, even better. That’s not scarcity. That’s respect for nature’s rhythm.

But for models like this to truly thrive, they can’t remain rare. The future of spirits—and of agroecology—shouldn’t belong only to the few who can afford to produce, distribute, or consume within an ethical, small-scale model. It belongs to all of us. In a global market where premium often equals exclusion, increasing local consumption and demand can shift the rules. If more people choose spirits that tell a story of place, plants, and people, we create pressure from the ground up—opening space for small producers without waiting for large corporations to cede it. Astrafilia shows us what’s possible. The real challenge is turning this growing current into something powerful enough to reshape the norm.

The portfolio breakdown: Granicera Gin and Maleza Liqueurs and bitters

Astrafilia’s Granicera gins are crafted in small batches, beginning with a one-month maceration of over 30 botanicals in corn-based alcohol sourced from Chiapas. The botanicals are enclosed in large, tea-like mesh bags and, after infusion, are pressed using a manual press. The liquid is then double distilled with steam in copper stills, a process that preserves the integrity and complexity of the botanicals while staying true to Astrafilia’s artisanal approach.

– Granicera Cítrica: crafted with 30 botanicals and a base of heirloom corn spirit. Botanicals are macerated in large tea bags, pressed, then distilled in copper stills.

– Granicera Floral: infused with Mexican flowers like melisa and purple toronjil.

– Granicera Herbal: featuring cardamom and Mexican oregano.

– Granicera Especiada: a post-distillation maceration with cacao, rested in darkness to infuse deep notes. This process highlights the uniqueness of each plant, and how careful handling—light exposure, resting time, alcohol strength—can bring out specific aromatic profiles.

Maleza, the liqueur line features seeds, flowers, and combinations of traditional flavors. These include:

- Maleza Cacahuate: macerated for 16 weeks, with sesame seeds tatemado on a comal, and coriander. It evokes a traditional Mexican peanut brittle or palanqueta.

- Maleza Cempasúchil: made with pericón flower, allspice, ginger, and cinnamon.

- Maleza Pepita: a blend of epazote, avocado leaf, papalo herb, and marjoram—like the base of a pipián or mole verde.

- Maleza Achiote: with annatto seeds, lime peel, and habanero; it tastes of orange with a spicy finish.

- Maleza Tejate: inspired by a traditional drink made with the seed of the mamey fruit, lightly toasted and blended with cacao flower—an earthy, almond-forward profile reminiscent of fernet.

- Maleza Bitters:

- Hierbas Mexicanas: made with avocado leaf, hoja santa, pennyroyal, pápalo, bay leaf.

- Flores Mexicanas: made with cempasúchitl, purple toronjil, white toronjil, sweet mace, lavender, grapefruit, damiana, sag.

- Especias Mexicanas: made with cacao, tobacco leaf, allspice, cinnamon, clove, coffee, pasilla chile, charred tortilla.

- Cítricos Mexicanos: made with Yucatan lime, Persian lime, tangerine, lime leaf, cilantro seed, lemon verbena

- Tonic syrup: A natural tonic syrup made with red and yellow cinchona bark, inspired by 19th-century apothecaries and 1920s soda fountains. Crafted by hand with over ten botanicals—including citrus peels, lemon verbena, rosemary, damiana, coriander seed, and chamomile—and sweetened with agave honey.

Leave a Comment