Bacanora tourism may be a way to help save a way of life. Laurel Miller gets off the beaten path to learn about Sonora’s famed regional mezcal.

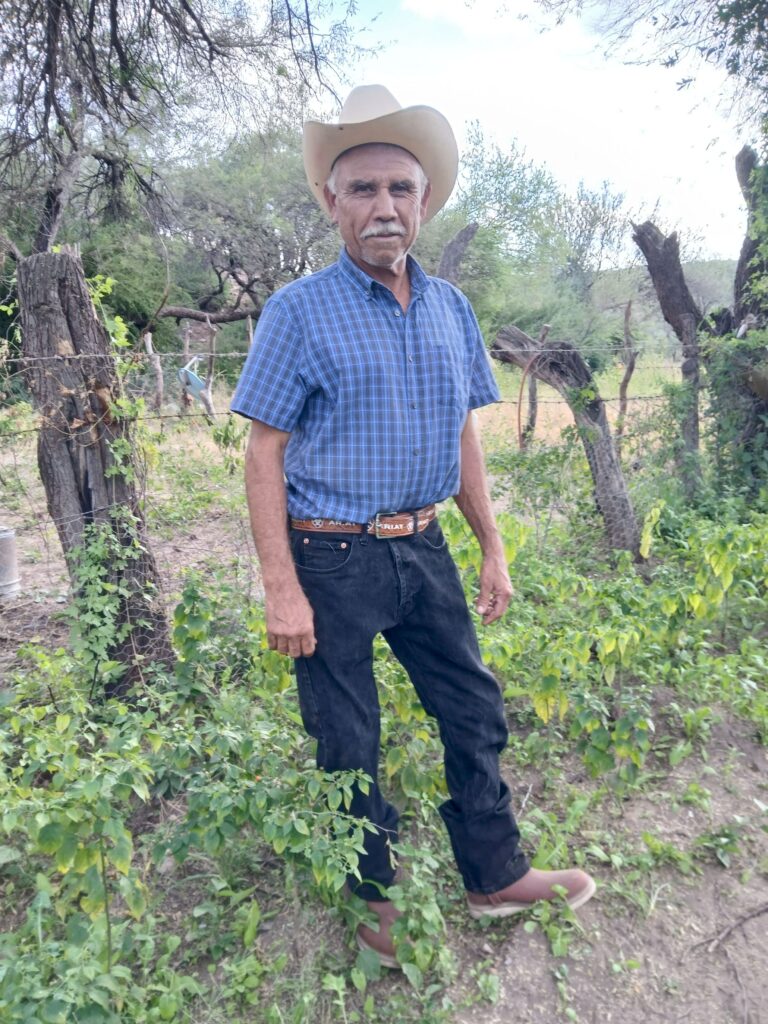

On a small rancho outside the northeastern Sonoran village of Bacadéhuachi, Jorge Valencia cautiously lifts a corroded sheet of metal off a rock-lined pit. A phalanx of rusted rebar and metal fence posts form a second barrier should anyone, including the resident burro, accidentally tread upon the makeshift cover.

Valencia is a fourth-generation vinatero, or bacanora distiller, and our group of 12 has gathered at his vinata to learn more about the tradition of distilling Sonora’s enigmatic agave spirit.

What is bacanora?

Bacanora is a regional mezcal with its own Denomination of Origin (DO), meaning it can currently can only legally be produced in 35 municipalities throughout eastern Sonora. Made from A. angustifolia haw (colloquially known as pacifica, espadin, or yaquiana), bacanora typically exhibits herbaceous, earthy, and mineral qualities.

Although I’ve been visiting Mexico since childhood and written about spirits for over 20 years, I’m a relative latecomer with regard to appreciating mezcales. Like many of us, I had traumatic youthful experiences with a Gusano Rojo and a certain brand of reposado tequila, and it wasn’t until I was moved to Austin that I had an agave epiphany at Mezcaleria Tobalá, thanks to the tutelage of the bar manager. I’ve been writing about agave spirits ever since and even ended up working at a sotol distillery for a time.

The Borderlandia backstory

That said, bacanora was fairly new to me, so I recently joined Borderlandia, on one of their bi-annual, four-day “Bacanora Route” tours. I was eager to learn more about the spirit, as weel as Sonoran food and culture. Experiencing that with a non-profit company that describes itself a “binational organization committed to building public understanding of the borderlands*” appealed to me.

Borderlandia co-founder Alex La Pierre, a native of San Diego, says he “fell in love with the Sonoran people, land, history, culture, and incredible cuisine” in 2014, while participating in a University of Arizona ethnographic field school held there. Soon afterward, he began working for Tumacacori National Historical Park near Nogales, where he met his future wife (and Borderlandia co-founder) Rocio La Pierre at a workshop. The seed for Borderlandia was sown.

“For the last two decades, the media has equated Mexico with violence and narcos, and as a result, many Americans have developed an irrational fear of the country…[At that workshop], I saw all the positive outcomes that arose from Americans and Mexicans interacting,” says La Pierre. “Rocio is from Hermosillo, and we started Borderlandia in 2019 to share positive information about the borderlands through cultural experiences that facilitate understanding of the region.”

Borderlandia’s most popular tours focus on Sonoran cuisine, including a food tour of Hermosillo and a Nogales taco tour. “We leverage food and drink as a bridge to connect Americans with Mexico and build cross-border relationships,” says La Pierre. “It was a natural fit to offer a tour focused on bacanora, which is Sonora’s only denomination of origin product and a symbol of the resilience of its people.”

The company, which is based in Tumacacori, Arizona, offers Bacanora Route tours in spring and fall. Each route typically features several vinatas in eastern Sonora. The traditional economic activities of the region are mining, agriculture, and ranching, combined with value-added products like leather, carne seca, and machaca (salted, air-dried beef and shredded dried beef, respectively).

La Pierre’s underlying goal for Borderlandia’s bacanora tours is to demonstrate that sustainable tourism can become a new form of economic activity in the Sierra Madres and hopefully motivate younger generations to stay in the region. Since the mid-20th century, there has been a shift in population from the mountainous eastern region to western Sonora, due to more plentiful jobs and higher pay. Older ranchers and farmers are dying off, and there isn’t a younger workforce to replace them. The net result is a loss of traditional economies, food shortages, and depopulation of villages.

Our trip is focused on the Moctezuma and Bavispe River Valleys of the east, but we convene in Nogales, Arizona, and cross the border to meet Borderlandia’s longtime driver Adolfo, a nattily attired man with a comfortable passenger van. I’m one of a few newbies on the tour, the remaining participants comprised of Borderlandia regulars from Arizona who come to discover new vinatas and explore more of Sonora. They’re also La Pierre stans who frequently rib him and regale the rest of us with amusing stories from past trips.

A three-hour drive takes us through terrain that morphs from undulating hillsides populated with native walnuts and oaks to flat thornscrub. Eventually, Hermosillo, where we’ll spend the first and last nights of the tour, looms on the horizon, shimmering in the heat.

After we check in to our hotel and undertake a bit of sightseeing–narrated by La Pierre–we enjoy craft beers at Buqui Bichi Brewing, followed by a feast of succulent carne asada at Tacos de Armando. Despite the brevity of our stay, I’m impressed by Hermosillo and the way the city has melded its colonial architecture and history with the trappings of modern, urban Mexico. Still, I’m eager to head east, to rural Sonora.

We set out on the Ruta del Bacanora

The next morning, we’re joined by Joan (Jo-AHN) Coronado, founder of Hermosillo’s La Ruta del Bacanora. Coronado’s paternal family makes bacanora under the label Siete Coronados; the vinata is a scheduled stop on select Borderlandia routes. He started his guided vinata tours out of the same desire as La Pierre, to create tourism and economic development in eastern Sonora. The men began working together in 2022 and have since developed seven bacanora routes that focus on Sonoran culture.

All Borderlandia tours include visits to various colonial-era pueblos, historic sites, artisans, and notable restaurants. Traveling on my own, I’m more likely to seek out a great street food vendor than a church or museum, but given La Pierre’s encyclopedic knowledge of Mexican history, the side trips add context to the tour and provide a deeper understanding of Sonora.

Our breakfast stop is classic Sonorense cuisine—gorditas topped with requeson (a fresh cow’s milk cheese similar to ricotta), machaca con huevos, and green corn tamales. Then we’re on our way to Moctezuma and our first vinata. En route, Joan tells us the Mexican government has proposed a controversial expansion of the production region to bolster local economies and tourism.

Adolfo pilots the van down a long, rutted dirt road. Many vinatas are located off the beaten track, which is more design than accident, a holdover from bacanora prohibition, which lasted from 1915 to 1992. In those days, getting caught distilling the spirit was punishable by jail, or worse.

When we arrive at Bacanora Andrade, we’re greeted by founder/vinatero Diario Andrade and his brother Carlos. The siblings run the small, seven-year-old distillery with their brother Noel, but their family has been producing bacanora for home consumption for generations.

Diario Andrade is an agronomist by profession and a self-taught vinatero; the increasing American appetite for agave spirits inspired him to begin producing bacanora commercially for export. Bacanora Andrade is now available in Arizona and California, as well as Hermosillo.

Bacanora Andrade is located in a modest warehouse surrounded by oaks, mesquite, and cattle ranches. The vinata also has a greenhouse with 50,000 agave pups grown from wild seed. The plants will take seven to 14 years to reach maturity; until then, the brothers will continue sourcing from a local grower. The vinata also sells pups to other vinateros.

Amid the faint strains of norteño from a nearby horse race, Diario walks us through his distillation process. The whole piñas are roasted in an outdoor pit lined with volcanic rocks, then chopped and added to the fermentation tank inside the warehouse. Depending upon the weather, the fermentation process, which uses ambient yeast, will take anywhere from four days to four weeks. A cot set up next to the wood-fired hybrid still enables the siblings to keep overnight watch of the entire process.

“A good bacanora should also smell like agave,” says Diario. “When tasting, some people hold it in the mouth before swallowing to stimulate the salivary glands and heighten the flavor.”

Most of my admittedly limited previous bacanora experience in the US has left me with the overall impression that the spirit tastes akin to gasoline. Happily, Bacanora Andrade exceeds my expectations and reframes my opinion.

Consumed neat, the pleasantly herbaceous spirit blooms hot on the palate at first, culminating with a clean, silky finish. While we sip and purchase bottles, I ask Diario his opinion of the proposed restructuring of bacanora production regions. He doesn’t hold back.

“The government wants to create more opportunities for families, but we’re frustrated by the proposal,” he says. “Our region was the most affected by prohibition, so we believe that the vinatas here, along with the other 34 municipalities of traditional production, should benefit the most from bacanora. These areas also continued to distill through all 77 years of the ban, even under threat of death.”

A bacanora day in Bacadéhuachi

Day three begins with a hearty breakfast at the Moctezuma home of Francisco and Irene, a sweet, gracious couple who earn their income by cooking meals for Universidad de la Sierra Sonora students living away from home. Fortified by copious amounts of café de olla, tortillas, and machaca con huevos, we depart for the tiny village of Bacadéhuachi, two hours to the southeast.

The landscape of eastern Sonora is stunning in its desolation. We pass through fertile river valleys, foothills teeming with oak and mesquite, and rocky outcrops and mountains rife with organ pipe cactus, saguaro, and ocotillo. Aside from the occasional sleepy pueblo, it’s a sparsely populated region informed by vaquero culture and the harshness of its climate. During the drive, La Pierre explains how these cultural and geographical traits led to the creation of a cuisine distinct from much of Mexico.

“Sonoran food is borne of preservation,” he says. “It got its start in the missions, where the goal was to stretch meals to feed everyone, which is why soups are so popular here despite the heat. Everything must be able to withstand the climate and a lack of refrigeration, which is why dried beef is so popular.”

Because wheat is a major crop, flour tortillas reign supreme in Sonora. Soups and stews like caldo de queso and gallina pinta are staples, and wild chiltepins—tiny, blisteringly hot red chilies —are the seasoning of choice. There is also some Chinese influence from late nineteenth and early twentieth century immigrants who came to work in agriculture and mining, which explains the popularity of soy sauce and cross-cultural dishes like a highly spiced “Chinese chorizo.”

After a night of too much bacanora, the Sonorense remedy of choice is menudo blanco with chiltepin or cahumanta (also known as caguamante), a spicy, tomato-based soup traditionally made from sea turtle. Because sea turtles are now a protected species, cahumanta is instead made with manta ray. Despite the distance from the Sea of Cortez, it’s common to see roadside caguamante stalls in eastern Sonora, all the better to ease the pain of an agave-induced hangover.

Bacanora isn’t traditionally served with accompaniments or used in cocktails. But Coronado, says bacanora tasting rooms are increasingly offering and selling regional delicacies like carne seca or walnuts, which grow prolifically in and around Nogales.

All of the food talk leaves us primed for our visit to Valencia’s rancho outside of Bacadéhuachi. When we arrive, his wife Tonya and their daughter are preparing lunch in the outdoor kitchen attached to the family’s hand built, one-room adobe house.

Bacadéhuachi is a 381-year-old village and significant bacanora producing area in the scenic Bavispe River Valley. Valencia, 63, began distilling as a teenager, when the spirit was still illegal. As such, he’s a supporter of the government’s plan to expand production. “Then there will be more bacanora for the people,” he says by way of explanation.

Valencia’s bacanora, made with the help of his nine sons, is produced under the label Mezcal del Coke, “Coke” being a popular diminutive of the name Jorge. Because wild agave has been overharvested in the region, he purchases agave from a nursery in a neighboring pueblo.

Like many vinateros, Valencia has neither the means nor the desire to utilize high-tech machinery, instead relying upon knowledge handed down by his family. Unlike Bacanora Andrade, the vinata is a simple, outdoor affair, consisting of nothing more than three pits and a handmade, wood-fired still fashioned from an old 50-gallon oil drum. Mezcal del Coke makes only two to three 80-liter batches a year, so Valenica augments his income by growing beans and other crops and allowing other vineros to use his vinata.

Valencia roasts his piñas in an earthen pit for two days, then moves the agave to a rock-lined fermentation pit that is supplemented with mineral-rich water from the rancho’s own spring. “Jorge’s bacanora is very pure, partly due to the water source,” says Coronado. “There’s no additives, no hangover.”

Valencia distills between December and May, when the cooler temperatures allow for better control of the ferment, which utilizes ambient yeast. After 10 to 12 days, he transfers the mash to the still.

The fermentation pit lends a potent earthy minerality to the bacanora, making Mezcal del Coke something of a cult product. Visitors frequently show up at the vinata, having learned about Valencia’s bacanora by word of mouth- something we experience firsthand.

After tasting, we purchase bacanora and bags of Tonya’s tortillas, cookies, and homegrown dried chiltepins. Then, we gather at outdoor tables for a lunch of pozole and braised pork with the family. Soon, it will be time for Adolfo to drive us up and over the mountains, and down into the intense heat of Hermosillo, worlds away from the hardscrabble existence of most vinateros.

While intrepid tourists can certainly visit commercial vinatas on their own, what Borderlandia offers (besides translation) is a far more intimate look at what compels multigenerational vinateros to continue making bacanora despite various hardships. Even in the face of proposed changes to DO regulations, tariffs, depopulation, and agave shortages, they carry on as a way to maintain family legacies, Sonoran tradition, and cultural heritage. Being a vinatero is an identity, not merely an occupation.

Borderlandia’s next Bacanora Route tour will be offered April 12-15, in conjunction with Tucson’s Agave Heritage Festival. The trip will include visits to the town of Bacanora, and Sahuaripa, home to the Mexican jaguar conversation group La Tierra de Jaguar. For more information, visit borderlandia.org.

*In addition to tours on both sides of the border, Borderlandia also offers workshops and lectures.

Leave a Comment