At a mezcal bar in New Orleans, novelist Yuri Herrera and contributor Holly Devon explore the menu, the city’s Latin American layers, and what the legendary Mexican president was up to during his lost years in Louisiana.

In his spectacular mural, Pan-American Unity—a visual manifesto if ever there was one—Diego Rivera paints the grand epic of the Americas in many colors. Caught in its majestic sweep are builders of skyscrapers and indigenous potters, vistas of blue sky and great lakes, locomotives winding through mountain mines, mythic temples and modern factories, and the pyramids of Teotihuacan. Yankee businessmen oversee construction, earth-brown high priests sit in a sacred circle, and muscular workers, conjured spirits, high divers, and a rainbow snake god all take their place. In the glorious story of the Americas, no character is left out. There is no discernible material hierarchy, no flags, nary a hint of national borders. Just the exquisite cataclysm of the American encounter, and power in a multiplicity of forms.

How the United States stole America

The United States of America doesn’t like to tell the story that way. Regional dominance is the only Pan-American unity that ever interested those who walk the Yankee halls of power. And as if the US economic and military chokehold weren’t enough, somewhere it was decided that language too must be conquered. How else would the word America become the exclusive province of the United States for English speakers? Amerigo Vespucci never signed the Declaration of Independence or ate apple pie with a Kraft single melted on top. While the Florentine explorer was encountering his future namesake on behalf of the Spanish and Portuguese, England was bankrupting itself with endless wars of succession, and Washington D.C. was in the hands of the Powhatan Confederacy. But against all reason the word America remains the imperial property of the only country, among 35 with an equally legitimate claim, that feels the need to keep the word for itself.

A city that defies borders

In the long years since the US adoption of the Monroe Doctrine, this attitude has seen few signs of improvement. Quite the contrary; on the gringo side of the border, maintaining Pan-Americanism á la Diego Rivera only seems to be getting harder. This is true even in New Orleans, which has always offered citizens of the United States a kind of in-country exile, a place slightly beyond the reach of the federal paradigm. Often referred to as the northernmost Caribbean city, to call New Orleans a Latin American city would be equally accurate. The city has always been a site for American convergence. When Spain took possession of New Orleans from France in 1763, it was a disintegrating backwater masquerading as a colonial capital. The crown’s intervention brought Louisiana’s failing plantation economy into the 18th century, built up its infrastructure, and created new economic and political connections that tied it to the Spanish empire.

When the borders changed, the connections remained. The Louisiana Purchase may have technically signed New Orleans over to the United States in 1803, but the city was too accustomed to belonging to itself. Ever since, the US has struggled to assimilate this quintessential Creole city into their American project. The struggle rages on; the city still belongs to itself, but it is forever fighting off northern encroachment. And, if recent headlines are anything to go by, the Anglo-Saxon American agenda is gaining ground.

As of December 1st, the President has sent border agents into New Orleans for a major immigration offensive answering to the name of ‘Swamp Sweep.” Governor Jeff Landry welcomes the federales with open arms and is vociferous in his threats to discipline the unruly city should its residents choose to resist. Many people have already gone into hiding; our most popular neighborhood taqueria has closed indefinitely, and will reopen only when the proprietors feel their customers and employees will be safe. Concerned citizens weigh their options, which are few and grim. The forces of isolationist extremism are armed, dangerous, and quick to suppress dissent. Upon invasion, the absurdity of isolationism will become a secondary fact to the full weight of the military machine.

A New Orleans mezcal bar with spirit

Fortunately, those who refuse to live within lines drawn by the nation state will surely continue to outnumber the opposition. Come what may, we will find a way to congregate. Wander into Espíritu: Mescalaría and Cocina in New Orleans’ Central Business District, and you may not immediately recognize it as a hub for Pan-Americanist subversives. Located in what might be uncontrovertially referred to as New Orleans’ most charmless neighborhood, its interior is warmly lit and stylish, if a little boilerplate. That said, there’s a subtle sincerity to the bar’s decor, and a less subtle sincerity in a short film kept on loop that brings the agave fields into the room, respectfully depicting the labor that goes into artisanal mezcal production. And then there’s the mezcal selection: its astonishing breadth and focus on small producers. The menu represents just about every mezcal-producing corner of Mexico, along with raicilla, bacanora, and sotol.

My drinking companion this evening is the Mexican-New Orleanian writer Yuri Herrera. He’s from Hidalgo, and he’s sipped more than his fair share of mezcals all over Mexico, though perhaps he’s never heard so much about agave terroir until tonight. Our bartender is a young New Orleanian of Puerto Rican extraction, and an enthusiastic mezcal scholar. She lights right up as soon as she clocks that we aren’t just here for a quiet cocktail, but rather are seeking a guide through Epíritu’s overwhelming menu. She sets to work collecting bottles from the shelves, until her arms are dangerously full of rattling glass. Setting them down in a row in front of us, maybe a dozen or more, she proceeds to give us the life story of every one.

There is talk of ancestral vs. artisanal methods and the costs and benefits of a Denomination of Origen for small producers. The passion is obvious in our young professor, and she anthropomorphizes the mezcal in a way I respect. She plays favorites—I end up with one—but she seems to truly appreciate the individual personality of each. We’re learning a lot on our way to the first drink of the night. But eventually, all this mezcal talk makes us thirsty. When she turns to help another customer, we make our selections so we can pounce with our order when our bartender returns—before another bushel of bottles can be brought out.

I go with the Akul Cirial, and Yuri takes the Mal Bien Papalote. Our choices suit us. Mine is fiery and all over the place; the flavors in his are sharper and more resonant. Settled now and happily sipping, our attention naturally returns to writerly things. It’s a pleasure to be in the company of a craftsman who really knows the job; his stacked resume includes five novels, a book of short stories, and contributions to literary publications like the distinguished Letras Libres and the cult favorite el perro. Yuri always has a few different projects simmering—recently, he composed lyrics for an experimental album whose songs represent, among other things, the colors of the Newtonian spectrum. My interests being similarly far-flung, we get right to business chopping it up.

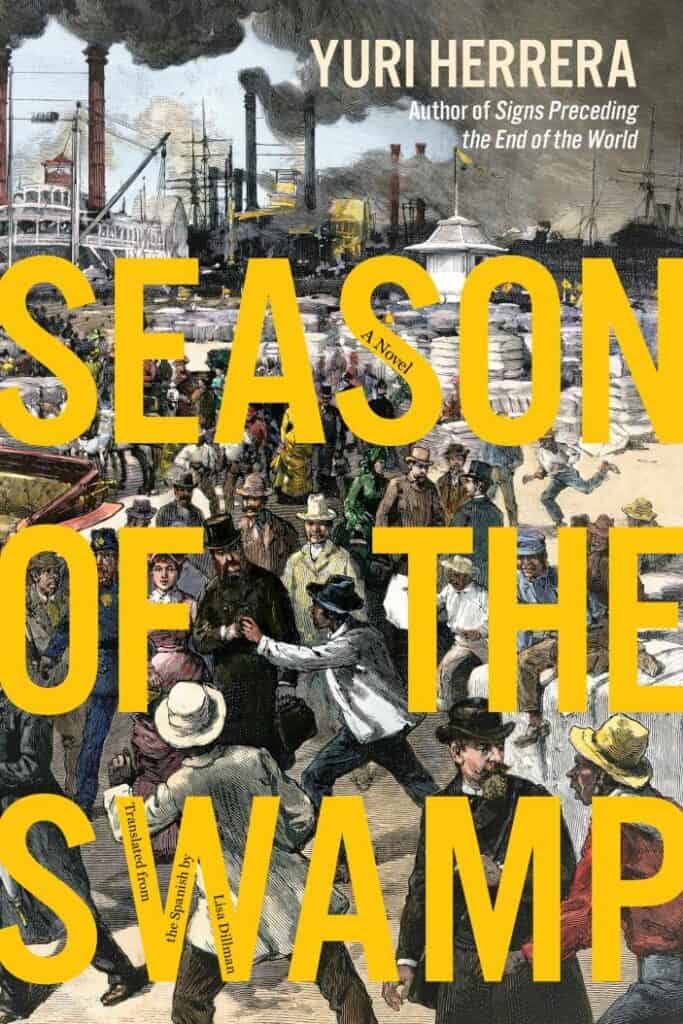

Season of the Swamp

But our literary affinity notwithstanding, there’s no denying that our professional pursuits keep us on different sides of the American cultural border. The division is evident in the lack of crossover between the goldmine of Latin American literary talent and US publishers. If you don’t believe me, try asking Yuri Herrera for a Latin American reading list. No matter how thoughtfully he chooses the material—and he does have a talent for this sort of thing—you will quickly feel in over your head, wishing your Spanish was better, lost in the vast ocean of American writers (south of the border) that no one saw fit to tell you about when you were still young enough to want to bite the head off whatever literary canon crossed your path. Artistic borders will always remain permeable, however, as long as you’re willing to make the effort. In the convivial atmosphere at Espíritu, the line between north and south adds welcome dimension to the conversation.

Yuri’s most recent novel, Season of the Swamp, follows Beníto Juárez during his brief period of exile in New Orleans before his rise to Mexican national politics. Set in 1853, the novel imagines Juárez in his full subjectivity, vulnerable as any stranger in a strange land. This is the novel’s first challenge; to humanize a legendary president whom Yuri describes as a “civic saint,” a presence that can’t be escaped–in Mexico, his name seems to be on everything. But for all the posthumous fanfare, his beginnings were decidedly humble. Born in a small village in Oaxaca where he spoke Zapotec as his first language, Juárez started his career as the rare lawyer who would defend indigenous villagers against the ruling class. Merging his personal ambitions with the fight for racial equality before the law, Juárez hit at vestiges of the colonial legal system everywhere he could.

Such pugnacious challenges to institutional power secured his place in the rising Liberal Party, and his fortunes rose and fell along with it. In 1847, Juárez assumed the governorship of Oaxaca, where a combination of even-handed justice and efficient administration earned him a national reputation for capable leadership. But when conservatives staged a coup and overthrew the federal government, Juárez and other prominent liberal politicians were driven into exile. Somehow some of them ended up in New Orleans.

Lacking the means of more aristocratic American rebels like Simón Bolívar, Juárez lived the life of a penniless immigrant. Perhaps this is why there is very little in the records about what he did while he was here. Someone of his status would have lived among the legions who took rooms in popular boarding houses, and he would have had to work. One of the few historical facts we know about his time here is that he made a living rolling cigars. On his daily commute to work in the French Quarter, Juárez joined the masses in the streets, and he did his drinking and dancing with the people, not locked away in the elegant courtyards of the well-to-do.

Politics is a prominent thread in Season of the Swamp; there are lively discussions throughout concerning economics and social justice, reason and progress, and other pillars of Liberal thought. But this is not a novel preoccupied with political heroics, or history as taught in textbooks. It hasn’t got much to say about the Plan de Ayutla, for instance, the document written by the New Orleans exiles in 1854 with the aim of removing the tyrant Santa Anna and drafting a federal constitution. At no point does the novel school you in mid-19th century Mexican politics. You get the sense that something important is happening that’s connected to the main character, but it’s not what we’re there to see. He knows he will return to Mexico when the time comes, and take his place leading the march of progress. In the meantime, however, he has accepted the challenge that New Orleans issues all newcomers—to fall into the tumult of a nationless American multitude, and try, at least, to join the dance.

The story begins with Benito’s first moments in the bustling port, when our hero is hit with the flood of sensation that would have greeted any new arrival. The reader is dropped there alongside him, starting at the docks, where our senses are overwhelmed by the muddy, malodorous, and dysfunctional. The sailors at his new lodgings spit “saliva, tobacco, and insults,” and get in deadly fights. He sees a dead body in passing. He is sickened by the normalcy of slave markets and chains. Violence is everywhere.

In this way, as in many others, the city hasn’t changed much. Yuri knows this better than most, thanks to his rigorous research for Season of the Swamp. With so few biographical details about his protagonist’s time in New Orleans—even in his autobiography, Juárez stayed almost conspicuously tight-lipped about his time here—Yuri had to turn to the archives to soak up as much of Benito’s New Orleans as he could. He read the newspaper from every day that Juárez spent here, from 1853 to 1855, focusing on the crime section. He says the crime has remained consistent from then to now, though back then, “There were a lot more stabbings.” I ask Yuri how researching and writing the book has impacted his visceral experience of New Orleans, and he says he’s not sure. “Maybe it has deepened it, in the sense that I have informed myself about the terrible and the marvelous that led us here.”

Paradox is ever-present in New Orleans, a place of beauty and decay, pleasure and torment, cosmopolitan sensibilities and stubborn provincialism. For Yuri, this is a feature of the city’s design. “It was absurd in itself to begin with, to create a city on top of a swamp,” he says. “So it’s this oxymoron of having an impossible city that’s at the same time existing, and all the time dysfunctional, you know?” I do know. Dysfunction defines daily life here, an unsurprising result of treating fluctuating layers of alluvial soil like solid ground; New Orleans geographer Richard Campanella describes it as the “topography of ooze.” From his authorial perspective, Yuri sees the city’s geological predicament as a creative well. “Another thing that I try to convey without saying it exactly, is that it’s a city constantly moving—meaning the literal ground underneath your feet. I think the symbolic underground is also constantly moving, and that’s something that is always feeding the cultural and social life of the city,” he says.

Besides the smell and the violence, Season of the Swamp leaves you with the memory of music. It’s playing everywhere, from the mysterious kind, where “sometimes you hear music but you have no idea where it’s coming from,” to an avant-garde concert by the seminal composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk. There are fiddlers accompanied by military drums, opera, and a “trumpet like a spike of wind at the coffeeshop.” Benito hears the “portent of drums,” has epiphanies of rhythm, and catches “parades, spontaneous parades that poured into the streets.” There’s something radical in all this music, and it carries into our conversation.

I ask Yuri what the roads that run between Mexico and New Orleans are made of, seeking to define the nature of our interconnection. “Music,” he replies. “The Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean has been an extraordinary laboratory for some of the most influential music of our time.” Truly, the contagion of music is the perfect foil for the quest to enforce political borders. It moves fast and free, and captures the true feeling of a moment in time.

I recognize a lot of my contemporary experience in Yuri’s depiction of 19th century New Orleans, from the way time swells and breaks in waves here, to the tendrils of story that weave their way around you through apparent coincidence, until you discern the patterns, evidence of some larger plot. Life here is difficult, and always has been, but the conditions make for a daring ecosystem of survivors. Far from all imperial centers, it’s a paradise for edge-walkers, who can breathe and bloom in this strange and pungent in-between world.

When I call New Orleans an in-between place, Yuri stops me, and offers an alternative perspective. He references the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène, who replied to a question about the European reception to his films by saying it shouldn’t matter what people on the cultural outskirts of Africa thought about his work. “Why should I be a sunflower and turn towards the sun?” Sembène posed to prurient Western audiences. “I, myself, am the sun.”

“Something parallel could be said about this place,” Yuri says. “It has created its own center, rarely understood by the French, who still think Creole is a perverted version of French, or Americans, who mostly can’t see outside of Bourbon Street and a few more clichés.” I concede the point—to consider yourself a denizen of the margins tacitly allows someone else the right to draw the lines of your reality. In this way, Yuri extricates New Orleans from empire, spiritually, at least. “It is a center that communicates with other centers in Latin America and the Caribbean, that have their own cultural wealth without asking for the recognition of the powerful.”

I begin brooding over the thought, concluding only that we can go no further into the conceptual labyrinth of the Americas without another drink. This time, we’re decisive as we place our orders. Thanks to the bartender, we are no longer intimidated by the menu; I tip my hat to women-owned brands by ordering the Hembra Tobalá, and Yuri breaks our Oaxacan mezcal streak with Parejo Sotól from Chihuahua. Our server has been joined by another woman, brisk and confident in a pretty blue dress. I speculate, correctly, that she is the owner, and introduce myself.

Haley Saucier rose to her current position from the ranks of New Orleans’s fighting forces of service industry pros. She was Espíritu’s bar manager before she bought the place, and the level up was a leap of faith firmly based in her passion for mezcal. When her former bosses found themselves too overextended for the many demands of running a small business, they hoped to avoid selling it to a restaurant group that would turn Espíritu into a margarita and chips joint. There were offers. But Saucier couldn’t bear the thought either, so when they presented her with an unbeatable deal, she took a breath and laid it all on the line. “My dad sold his Harley for the downpayment,” she says.

The margins are slim, and she’s open about her struggle as a small buyer hoping to provide a mezcal oasis in a state where knowledge of agave is basic at best. “When this place started, no one in Louisiana even knew what mezcal was,” she says. The limitations of the location make it hard to connect with distributors, and it’s no mean feat to establish a drinking culture around pricey imports in an impoverished city in the heart of Dixie. “Poor Louisiana,” one might say, paraphrasing Porfirio Díaz. “So close to Mexico, yet so far from God.” But in spite of the challenges, Saucier is dedicated to making Espíritu a place for mezcal awakenings, where learning is ongoing.

As far as my mezcal education is concerned, the plan is working. Saucier concludes our seminar with a dusty, nearly empty bottle she grabs from a high shelf. She found it, she says, after finishing the mezcalería’s transfer of ownership, and opened it to find that it had gone bad. At Espíritu they’re careful to keep an eye on the levels of mezcal in the bottles: if there’s too little left for too long it can oxidize, and lose its luster, or worse. She uncorked it to let us smell the unseemly funk, explaining that this contingency is one that other liquors don’t share. According to Saucier, it’s because “mezcal is alive.”

My final drink of the night might as well be the official cocktail of Season of the Swamp: a mezcal sazerac, the classic New Orleans cocktail with a Oaxacan twist, and the most on-the-nose application of my Pan-American thesis imaginable. But heavy-handed metaphor aside, the drink really is delicious. Though the particular flavors of a Sazerac make substitutions difficult, it’s as enveloping and fragrant as the original, but with a sharper, brighter finish. Without making too much out of swapping out liquors, I cannot deny this submission to the mountain of evidence suggesting that America’s promiscuous combinations produce magical results.

And good thing, too, since our promiscuous combinations may be all we have to counterbalance rising militarism, and the legacy of extraction. Protean and irrepressible, American creativity is the only force I know strong enough to lift the burden of our history. “Create is this generation’s watchword,” wrote Cuban poet and freedom fighter José Martí from Mexico City in 1892. “A vital idea set ablaze before the world at the right moment can, like the mystic banner of the last judgment, stop a fleet of battleships.”

The idea of Pan-American unity is both vital and audacious, drawing us closer together in defiance of a system that seeks to permanently drive us apart. It’s an idea I refuse to give up on. I live in New Orleans, after all, surrounded by the magic of the American encounter. It’s everywhere I look: in spontaneous street parades, in music emanating from mysterious places, and in conversations between like-minded Americans at a New Orleans mezcal bar, where the spirits they serve are alive.

1/15/2026: Note that Richard Campanella’s name was misspelled in the original post. It has now been corrected.

Wow!! That writing makes me want to go straight to New Orleans and have a drink at Espíritu !!, with Holly Devon!