Michoacán is a place defined by the movement of people, goods, ideas and whole families crossing borders in search of opportunities. In a vinata in Oponguio, the burn of wood beneath the still tells stories of staying, of returning, and of keeping a tradition alive no matter the distance.

I have been to Michoacán four times, whether in winter or the summer season—and almost always by car. After crossing the mountains, there’s a moment when the landscape opens and a deep green patch of trees and fields comes into view. The scent of wet earth fills the air, and the light seems to stretch longer across the land. It’s against this backdrop that I’ve come to understand the paradox of the state: a place overflowing with fertility, tradition, and culture, yet vulnerable to outside interests.

This past June, I returned to Michoacán with a small group of mezcal drinkers, writers, and digital creators, as well as the importer for Palomas Mensajeras mezcal. I’ve always carried some wariness about traveling through the state. Since the presidency of Felipe Calderón, Michoacán’s reputation has been shaped by national headlines, narratives that often overshadow its ecological richness and cultural depth.

Our tour included stops in Uruapan, Pátzcuaro, and Morelia, as well as time in the surrounding countryside. In each place, people were eager to share their culture and welcome us into their world. For me, coming from Mexico City, this felt like a quiet but powerful pushback against the narratives that often overshadow their lives. What I found was a Michoacán that persists, resists, and thrives through work, family, and identity.

A Family rooted in mezcal

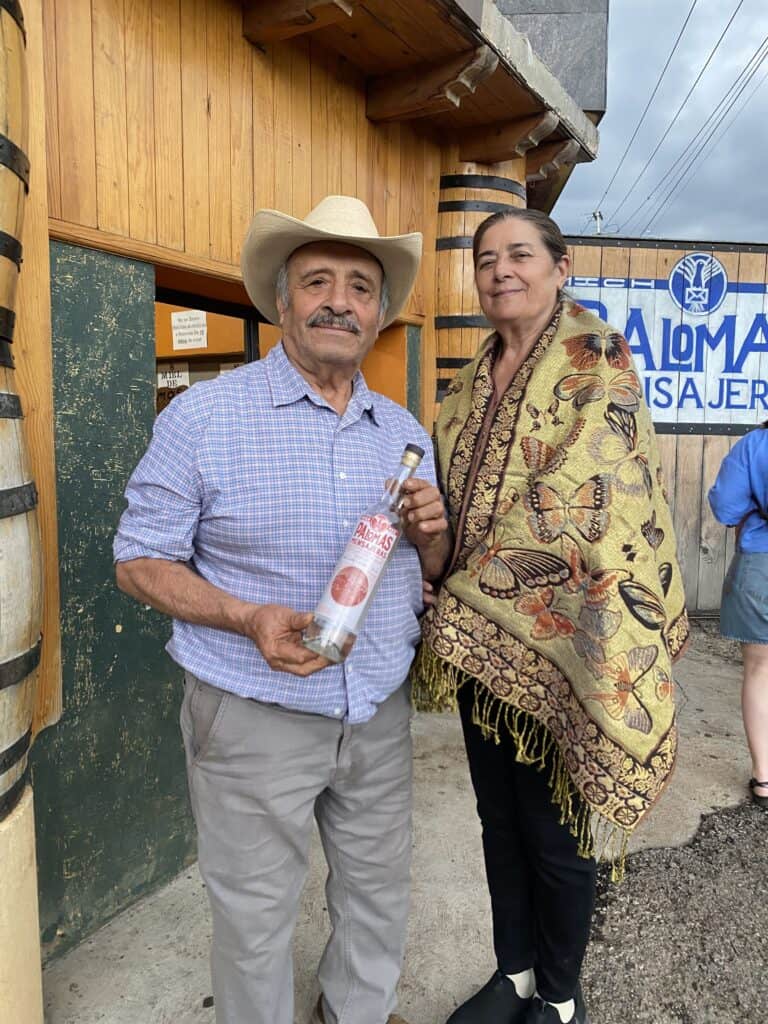

In San José Oponguio—just 90 minutes from Morelia—stands the vinata Palomas Mensajeras, run by the Pérez Reséndiz family, a lineage of five generations of campesino mezcaleros. At the center is Don Miguel Ángel Pérez Reséndiz, now 83, who began promoting Michoacán mezcal in 1997, when few outside the state even knew the name cupreata or understood the region’s distinctive Filipino-style stills.

In rural Mexico, farming has long been an activity of survival. Recent protests—farmers blocking highways to demand fair prices—reflect how government-guaranteed prices rarely cover operating costs. Against this backdrop, migration has often been seen as the only path toward financial stability.

So hearing the story of someone who chose to stay feels like an affirmation that rural life can still be viable.

Most of Don Miguel’s siblings and relatives left for Chicago, joining what is now an estimated 4 million Michoacanos living in the U.S. According to a study of the 2020 Census, one in every five residents of the Chicago metropolitan area is of Mexican origin, many with roots in Michoacán.

“People always told him, ‘Come to Chicago,’ because they knew how hard he worked,” says Esperanza Pérez, his eldest daughter. “But he decided to stay. He has always put mezcal first.”

“This land has given me everything,” Don Miguel tells me. “How could I leave it? Who would work my land if I had gone?”

His great-grandfather was the maestro vinatero at Hacienda La Concepción, in Villa Madero, a region recognized as the birthplace of Michoacán’s mezcal tradition. Since 1995, Villa Madero has hosted the Expo Mezcal —an event showcasing dozens of brands to crowds of 35,000 to 40,000 visitors.

From Villa Madero, Don Miguel and his wife Manuela moved to Oponguio, in the municipality of Erongarícuaro, where they founded their vinata and raised their family in the traditions of mezcal.

Heritage and innovation at the vinata

Their sons, Melitón (39) and Miguel (41), represent a bridge between heritage and adaptation. Their vinata is located right by the highway that takes you to the iconic lake town Pátzcuaro. We were welcomed with a table set up for a tasting of all of their expressions:

- Chino (local name for cupreata) cultivated and grown in Etucuaro

- Alto (inaequidens) grown wild in Oponguio

- Ensamble (cupreata, inaequidens, rhodacantha)

- Cenizo

- Azul

While the cupreata and ensamble have been widely embraced in the US, the family is excited about their newer experiments with cenizo and azul, often the result of exchanging seeds with other producers. They currently produce around 18,000 liters per year and began exporting in 2023.

Their distillation setup is one of the most fascinating parts of the vinata. Michoacán has long used a local adaptation of the Filipino still, a system that América Delgado describes in Mezcalla (p. 114) as “originally a rustic distiller made from two clay pots stacked on top of each other. It is a form of internal condensation, because the vapor cools and condenses inside the still, and the resulting liquid is distilled again.”

At Palomas Mensajeras, the still is a hollowed-out wooden trunk assembled like a barrel without a top or bottom. The internal architecture preserves the principle of internal condensation, but the materials reflect generations of trial and adaptation.

As a creative response to the scarcity of young labor, Meli has installed electric pulleys to lift still covers and continues to use his father’s ingenious 1979 Datsun gasoline engine, repurposed to power a one-of-a-kind shredder. In a fiercely competitive market, innovation is not a luxury—it’s a survival strategy.

The process: fire, fiber, fermentation

Fermentation lasts 5 to 8 days (up to 15 in cold months) in stainless steel or food-grade plastic. The fibers are shredded in the homemade machine and cooked in a wide brick-lined pit unique in the region—it is fired with pine and green oak for 12 hours. Around 300 kilos of Agave cupreata roast under tule mats. From 400 kilos of maguey, they produce roughly 70 liters of 47% ABV mezcal—each batch shaped by weather, agave maturity, and sazón.

While some of us were checking the stills upstairs, a few others wandered down to see how they were starting the fire. It was only then that I realized how easy it is to overlook this part of mezcal production. Tending the fire is rarely discussed, yet it is one of the most essential steps. At this vinata, it all begins by using ocote—a highly resinous pine used throughout Mexico to start fires—a step they call enhuacalar. Meli explains that they always begin with pine because it catches quickly and burns hot, then finish with oak, which burns slower and steadier. The job is equal parts precision and intuition: tending the fire, feeding the wood little by little, and then climbing the stairs to the upper platform to check the stills and ensure they are properly sealed so no steam escapes. It’s meticulous, physically demanding work—especially when all three stills are running at the same time. And soon it will be even more intense: the family is preparing the space to install three additional stills.

Doña Manuela Pérez runs the vinata when Don Miguel is away. She and her daughters-in-law make delicious cremas with fresh milk and different flavors such as pine nut, coconut, and local fruits, as well as more commercial ones like Mexican marzipan (mazapán). Between distillations, we shared pollo en vara—chicken marinated in sour orange and spices, skewered on a wooden vara and cooked over an improvised fire next to the pit oven. It was served with homemade Russian salad. It felt like a comida cotidiana, an everyday meal that wasn’t staged hospitality—it was a family lunch. In this vinata, the kitchen and the still coexist as one continuous space of labor and care.

Michoacán in context

Michoacán remains one of Mexico’s agricultural powerhouses. It produces 3.8 million tons of avocados, limes, guava, and berries annually, and ranks fourth in national agave production. Yet abundance also brings challenges: disputes over land and water, pressure from agribusiness, and limited infrastructure for small producers.

According to COMERCAM’s 2024 report, Michoacán is 3rd in mezcal export volume but only 8th in national production, a revealing split that underscores its export-driven potential.

In this context, Palomas Mensajeras embodies this: producing locally, selling nationally, and exporting to the US–without abandoning who they are or where they come from. Their expressions reflect the region’s biodiversity—earthy, herbal, unpredictable, vibrant.

What’s in the name?

Before leaving the vinata, I asked Don Miguel about the name Palomas Mensajeras. He told me it comes from a song called “Qué lindo es Michoacán.” In one verse, the singer calls to the palomas mensajeras—messenger doves—and says: “Si van al paraíso, sobre él volando están … Dios hace mucho tiempo que lo quitó del cielo, y por cambiarle el nombre le puso Michoacán.” It’s an ode to the land, a reminder that Michoacán is a paradise renamed.

But the name carries another resonance. In Michoacán, Palomas Mensajeras is also a government program that helps elderly parents—usually over 60 or 65—apply for temporary visas to visit their migrant children in the United States after decades apart. The program operates through state governments and consular support, helping families reunite under strict requirements: no prior illegal entry, no history of multiple visa denials. For many families, it is the only legal path to see loved ones again.

Palomas Mensajeras mezcal is, in every sense, about movement and return: about carrying news, memory, and culture across borders. This mezcal doesn’t just stay in Oponguio—it travels to Chicago and back, much like the people of Michoacán themselves.

The binational future of mezcal

As I stood watching the first drops of rain gather on the wide vinata windows, I found myself thinking about movement—who leaves, who stays, and what it means to live between two places. That reflection came naturally after Esperanza told me about David, her 21-year-old son, who is now in his third year of college in the US. He is already part of the family project, promoting Palomas Mensajeras in Chicago and helping his grandfather translate during their industry visits. They’ve noticed how much it matters when customers can speak directly with a producer—how trust, curiosity, and pride circulate in those encounters.

It was at that moment that the binational dimension of Palomas Mensajeras came into focus. In a state that exports fruit and mezcal—and people—the Pérez family remains rooted while still reaching across borders. Their ability to move fluidly between Michoacán and Chicago represents more than migration—it represents circulation. Just as bats pollinate maguey across long distances, families like theirs carry skills, capital, and culture back and forth. Each trip north brings bottles and stories; each return south brings resources, ideas, and hope.

Consumers in Chicago who buy their mezcal participate in a system that satisfies their palate while sustaining a rural tradition. What might happen if more families could move freely, collaborate across borders, and turn migration into regeneration?

With supportive policy and real access to markets, mezcal could become not just an export but a cultural bridge sustained by movement between two worlds. But for that to happen, the change must be systemic. In Michoacán, where organized crime intersects with different layers of government, people need the assurance of safety before they can truly build free enterprise. And on the other side of the border, the hardline measures coming from the U.S. offer only short-term, unilateral answers to a much deeper, shared reality.

Leave a Comment