Paloma Rivera is the founder of Tianguis Mezcalero, a project dedicated to the promotion of traditional agave spirits and the families who make them. She helps promote and distribute distillates from producer-owned brands such as Chacolo, Don Mateo, Aguerrido, Reyna Sánchez, Vinatero, Las Almas, Alegrías Campesinas, Andavete, and Tesoro de Atlapulco. Based in Mexico City, her work bridges humanism, activism, and emotion.

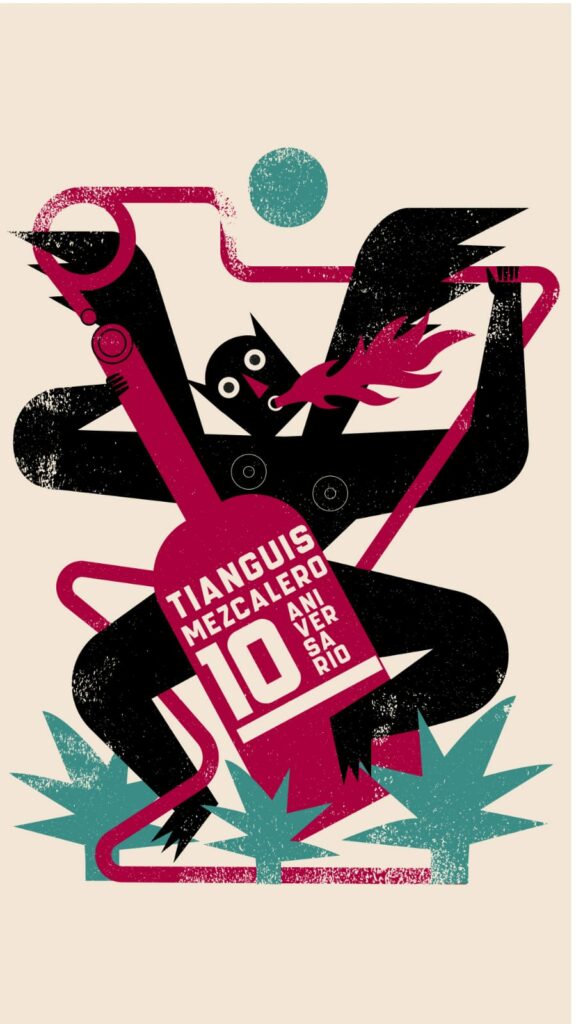

I met Paloma Rivera five years ago, when I attended one of her annual end-of-year events—a kind of posada organized by her project, Tianguis Mezcalero. I remember being struck by the sense of community, the quality of the food, the thoughtful curation of mezcal producers, and the guests’ willingness to pay for every sip or little vasito of mezcal they received. It was clear that something special was happening—something rooted in dignity, respect, and celebration. That event was just one example of the cultural programming Paloma develops through Tianguis Mezcalero. Beyond its anniversary gatherings, the project creates encounters tied to seasonality and collective memory: a Christmas sale with a posada theme, an 8M event for International Women’s Day, or participation in the Tigrada festivities from Guerrero each May, along with workshops, tastings, and appearances at other fairs. Together, these activities weave a calendar that keeps mezcal anchored in its social, cultural, and territorial context.

After reading her contribution in Miradas Femeninas del Mezcal, in which Paloma recounts how mezcal found her and became the thread through which she could recognize herself and craft her own story, I understood her relationship with the spirit: she was not an intermediary or just another chilanga selling mezcal. Through a personal timeline, she shares her experience as a woman within the collective testimonies of those who make or promote mezcal. Her narrative closes with a symbolic return to origin. She acknowledges that to speak of mezcal is also to speak of herself, and that her path seeks to create territory rooted in affection, collectivity, and memory. After hearing her speak at the book’s launch, I began following her work more closely. I don’t buy mezcal from stores anymore; I prefer to purchase directly from producers and, often, from her network. Her approach to mezcal is human, rigorous, and inspiring. I believe more people should know about her.

This interview is a window into her world.

Where did you grow up, what did you study, and what was your first job?

I grew up in Mexico City, in the Camino al Desierto de los Leones neighborhood. In childhood, I was very close to my paternal grandmother, whose stories and presence shaped me deeply. I studied Development and Intercultural Management at UNAM’s Faculty of Philosophy and Literature. That’s where I first encountered the maguey, and learned about its many uses. My first job was as a cashier at a chain restaurant when I started studying at the university.

Who is Paloma Rivera today? If you had to describe yourself in one phrase after all these years among mezcales, what would it be?

Back then, I never would have imagined I’d end up working in mezcal. It took years of living, reflecting, and learning to understand myself. Today, I see mezcal and maguey as forces that allowed me to rebuild and reinterpret my story—to understand where I come from, what moves me, what gives my life meaning. The people I’ve met along the way give me vitality. They make me want to live more fully.

In your essay for Miradas Femeninas desde el Mezcal, you describe your first encounter with this beverage. What did you see or understand in that moment that changed the way you looked at things?

My formal journey started at UNAM. I actually began in communications but switched majors and started working early. I met Eduardo Quintana, a professor who influenced me greatly. Through a job with a travel agency, I had to design a pulque route, which brought me face to face with the world of maguey. From there, someone recommended I meet Tío Corne from La Logia de los Mezcólatras. One of my earliest tastings was during the CONABIO “Agaves and mezcales” map presentation, and that’s when it happened: I tasted traditional mezcal for the first time, and a whole world opened up.

You started learning with the Logia Mezcólatra and their sensory methodology. Today you direct Tianguis Mezcalero. How have you translated that way of learning and sharing into your own project?

The mezcales I tried that day have become benchmarks—expressions and practices that are increasingly rare, rooted in a sense of time and place that doesn’t easily replicate. With Logia, I learned through the senses. It was a methodology that resonated deeply with me: learning through emotion, sensation, and embodied experience. I’ve never liked school. Not because I struggled academically, but because it felt like an obligation. The world of mezcal taught me that I learn best through love and emotion. Through music. Through stories. Through relationships.

The Tianguis Mezcalero is more than a market: it’s a space of encounter. What role does it play in your eyes for the cultural defense of mezcal?

The Tianguis Mezcalero is a project of proximity, born from networks that nurture alternatives. It’s a short supply circuit that emerged as a response to the voraciousness of conventional markets, where traditional mezcales had to name themselves in order to be distinguished from the industrial version shaping mainstream consumption. Our food systems are usually the opposite of short—dislocated, disconnected, stretched to absurd scales. That’s why we end up with packaged products from the other side of the world, stripped of their essence as food.

In this context, the role of Tianguis Mezcalero in defending mezcal culture is about attending to the social conditions that stem from historical and cultural ones, and about recognizing the living subjects we relate to in a web of affection, friendship, and mutual respect. If you truly care about someone, you act from that place—not from what you can extract from them or their production. Of course, we commercialize, distribute, send money back to families, and acquire debts. But what comes first is mutual support, the possibility of sustaining life forms that inspire us, and the desire to contribute to them and learn from them. That is why we have resisted living off mezcal alone—because not even the producers live only from mezcal. They also have other jobs and responsibilities. They are not just mezcaleros–they are much more.

So, the Tianguis is not only about preserving or defending; it’s about ensuring continuity—of spirits, of lives, of answers we find in them to our own questions. It’s a space for diversity. Today, as I direct the Tianguis Mezcalero, ten years after it was born from this emotional logic, I can say it is more than a market: It is a place of encounter and reconnection, where artisans, cooks, musicians, farmers, and anyone who comes feels welcome.

Have events always been at the heart of Tianguis Mezcalero? If so, why are they so central, and how has your approach to organizing them evolved?

When we first began in 2015, we organized the tianguis once a month. In 2019, with a new team, we took it up again in that same spirit—sometimes even hosting two in a single month, since there weren’t that many “festivals” around back then. But it was exhausting, and we realized we wanted to design cultural events that were more complete, consistent, and ultimately more effective for the producers. That’s why in 2020 we decided to hold them every three months. And then, of course, the pandemic came, and everything stopped.

By 2022, for our 7th anniversary, we returned. And looking at the current saturation and competition of commercial events, we’ve chosen to focus on what really feels good for the families we work with and for ourselves: one major annual anniversary celebration between May and June, complemented by smaller events throughout the year. These include tastings, collaborations with food projects rooted in history, and artistic initiatives—from visual arts to illustration and music—as well as our traditional December warehouse sale or mini tianguis. Up until today, we have created about 50 events.

In more than a decade, you’ve seen how Mexico is reconciling with its spirits. What good and bad changes have you noticed in how mezcal is consumed?

Over the last decade, I’ve witnessed Mexico slowly reconcile with its own spirits. There’s beauty in that. People are reconnecting with our drinks and our stories. But there’s also danger. The market values novelty, exotification. It turns cultural expression into a trend. For the campesino, mezcal isn’t new. It’s ancient, we don’t even know exactly when it was created. It is part of the rhythm of life. We need more people willing to resist the logic of extraction and build ethical economies based on the defense of life, not on profit.

You’ve said your story with mezcal is inseparable from your personal story. Looking back, what has this path revealed to you about yourself and the way you learn?

Over the years, I came to understand that school was never really my thing. Even though my grades suggested otherwise, I didn’t enjoy it, because it didn’t reflect my true way of learning. The mezcal world showed me that my real path is to learn through emotions—through affection, sensations, through the body itself.

I live from the emotions that mezcal generates in me. I’ve learned to approach it through life stories, through the struggles we often don’t hear about because privilege keeps us in a bubble. These stories are moving, humbling, and they push me to question my surroundings and my own position within them.

That’s why my personal challenge is always: How can I live up to the dignity, effort, dedication, strength, and character of the producers? In this journey, I ask myself: How do I honor their generosity, their contradictions, their strength? Because they are my teachers. They are the heroes of the field and the mountain. They are not perfect—they are human. But deeply admirable.This is the learning I try to transmit through high-quality spirits. It isn’t about idealization—it’s about admiration.

For someone wanting to enter this world, why do you believe an anthropological approach is vital? How can we avoid ripping mezcal from its context?

I believe any serious approach to mezcal must be human. More than “anthropological,” it’s about recognizing that there are many ways of knowing—each one valuable, each one distinct—and that some of them are very close to us if we take the time to listen. That’s what mezcal and its people need: for us to stop thinking of it as just a product.

That’s why I don’t really like the idea of “mezcales de autor.” Mezcal is never an individual creation; it’s a collective process, one rooted in history, in the intertwining of temporalities, in deep ties to territory. To separate the drink from that context is to strip it of its meaning.

Like our friends at La Rifa Chocolatería say: let’s stop contributing to the idea of anonymous products. Just like in the chocolate making process, behind every sip of mezcal there are people, stories, and landscapes. Our responsibility is to build emotional, not just transactional, relationships—relationships that honor the dignity of those who make mezcal and that keep the knowledge alive.

In a moment where the word “artisanal” is romanticized, what responsibility do we have as storytellers of mezcal?

In these times of commercialization and romanticization of the “artisanal,” we have a duty to tell its story responsibly. To name the people behind it. To speak from friendship and respect. Because to conserve mezcal is to conserve life.

Leave a Comment