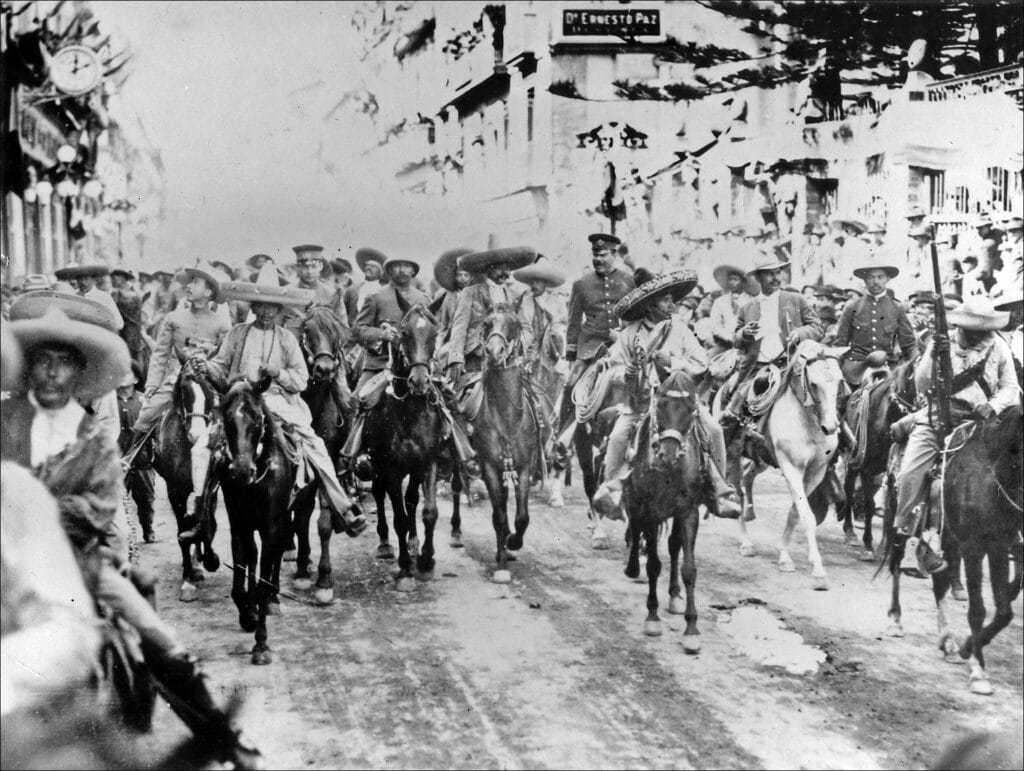

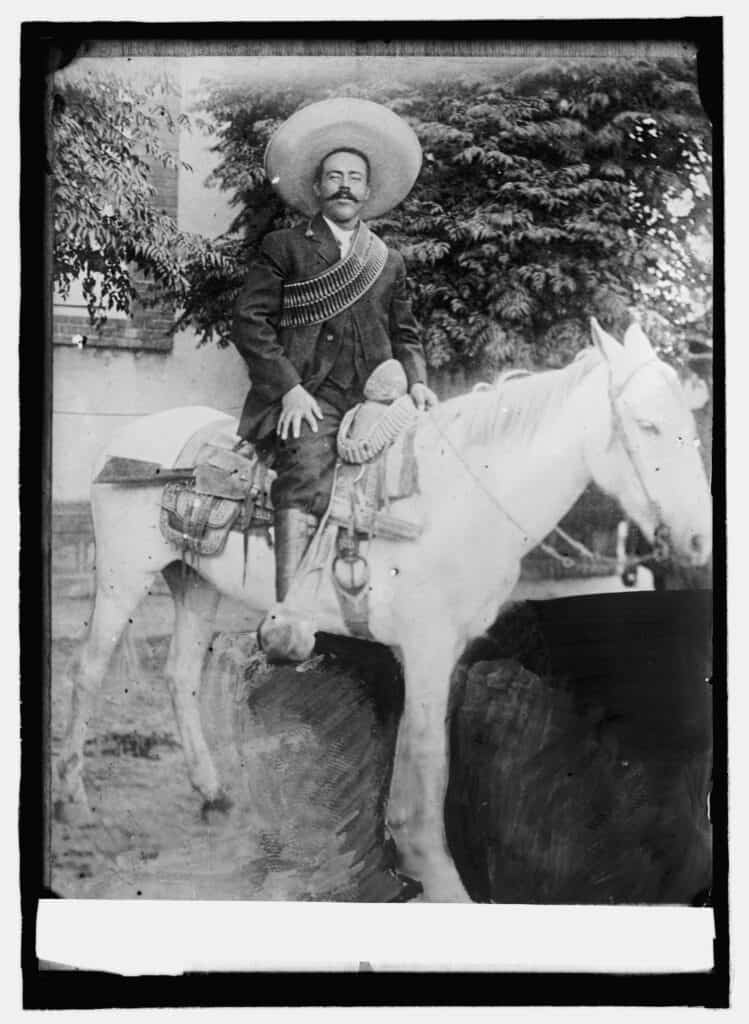

The year is 1914, and the great stage of history is set to perfection. After three years of fiercely battling for the soul of Mexico, the two greatest figures of the Revolution, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, arrive at the floating gardens of Xochimilco to meet for the very first time1. Their well-earned reputations as fearsome class warriors—Villa in the arid plains of the north, Zapata in the fertile land to the south—precede them to this auspicious meeting ground, where the city’s indigenous architecture recalls the splendors of Mexico’s pre-Colombian past. Just south of Mexico City, the chinampas whose bounty once provisioned splendid feasts for Mexica conquerors are no less verdant now. Flowers and colorful streamers adorn the banks of the canals, gifts from the people of Xochimilco to welcome their heroes. Keenly aware that the more conservative Constitutionalists are gathering their forces to press their advantage, Villa and Zapata have convened with the intention of unifying their armies. If they succeed, it will be the most formidable popular front in the Americas, and perhaps the world.

With Mexico’s future hanging in the balance, the two men sit down to the historic parlay without quite knowing how to begin. Eager to smooth over the awkwardness, Zapata calls for cognac, knowing a drink is the surest way to recover your footing in uncertain terrain. They need something to sip and hold in their hands, to give in to a spirit’s warmth and let it lighten the gravity of their meeting. Released from mutual discomfort, they might start to build the bridge between north and south, bandit and farmer, that will allow them to discover just how much common ground there is between them.

But there would be no salvation found in brandy that day. In one of history’s more unexpected twists, Pancho Villa was a teetotaler. He severely restricted drinking in his regiments, and unfailingly led by example. At the moment of truth, he chokes—literally, the moment the cognac touches his lips. Zapata looks down at his hands, embarrassed for them both.

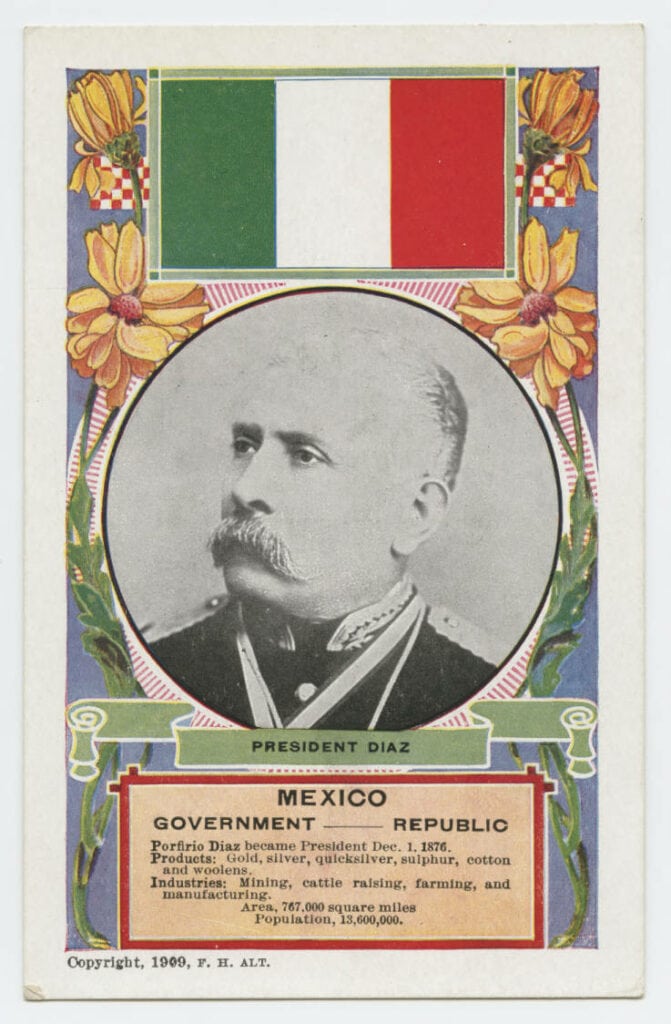

Before 1911, when revolt erupted throughout Mexico, neither men had any idea that they were headed for key leadership positions in the twentieth century’s first revolution. Born into the lower rungs of a class ladder they had few aspirations to ascend, their sense of Mexico hadn’t extended much further than their home regions. They were of a generation that had never known a leader other than President Porfirio Díaz, who ruled Mexico with a strong fist and a canny eye for over 30 years. In the Porfirian regime, power was limited to a tight-knit inner circle, articulated by the positivist intellectuals known as the científicos and exerted by the landed elite. These elites went along with the dictator’s pursuit of foreign capital and industrialization; in return, he made sure the quasi-feudal landowners, known as hacendados, had free rein to pursue their interests at home. In both cases, economic development came at the expense of the rights and lands of Mexican villagers2.

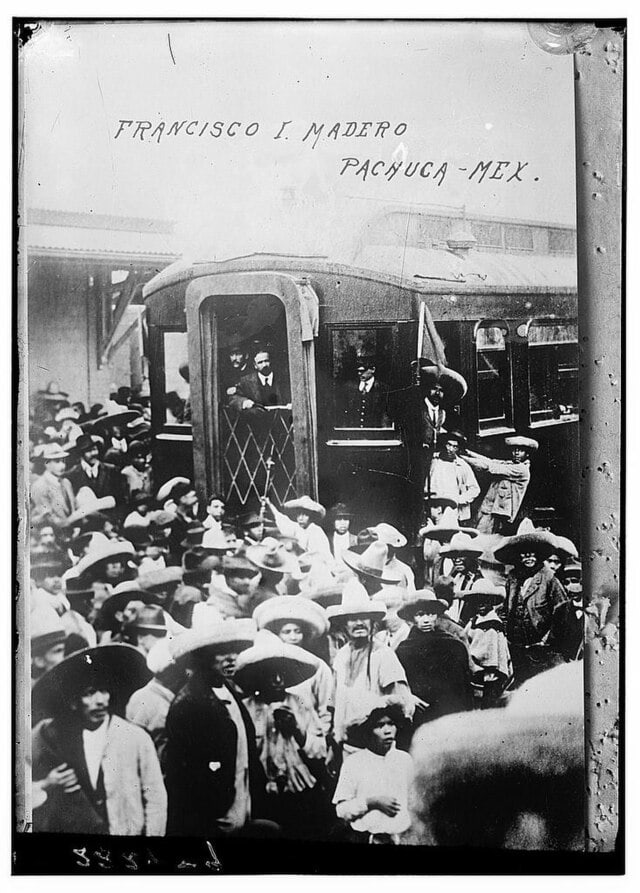

In 1911, the young, guileless aristocrat Francisco Madero staged a coup to prevent yet another crooked reelection of the aging Díaz. Madero’s liberal political agenda was in no way radical, and when newly-minted revolutionaries Villa and Zapata made common cause with Madero, he found himself ill-equipped to lead such a diverse coalition. As Porfirio Díaz said in 1911 while boarding a ship from Mexico to Paris, where he would live out the rest of his life in exile, “Madero unleashed a tiger, now let’s see if he can control it.”

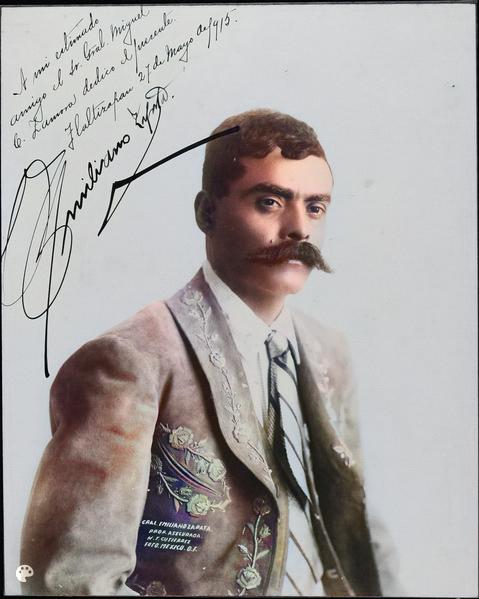

Amidst the fire and fury of the revolution, Villa and Zapata’s opponents cast them as vicious brigands, while their ardent supporters hailed them as revolutionary rockstars. Either way, sobriety hardly fits the image. However, if you asked anyone with a limited knowledge of the Mexican Revolution to guess which of the two abstained from alcohol, they’d probably point to Zapata as the likelier suspect. Strength of character was his calling card, land and liberty his true creed. In the long history of revolutionary leadership, Zapata may be the one man who never let the power go to his head.

This is probably because he never wanted it to begin with. Zapata was a man of his village, Anenecuilco, located in the heart of Morelos. Though the state shares a border with the Federal District, it is a world away from Mexico City. When the village was threatened by external political forces that its elder leaders struggled to understand, they elected Zapata, a man they trusted for his integrity, to guide them. His choice to join the revolutionary ranks was a last resort to save their way of life.

In the years preceding the revolution, the villagers of Morelos, whose ancestral connection to the land can be traced back long before the Aztec conquest, were getting dangerously squeezed. Morelos is just to the south of the arid Valle de México, but its ecosystem is tropical by comparison. The hacendados of Morelos were sugar planters, a notoriously land—and labor—hungry group, and they seized the arable parcels, forcing the villagers into mountainous terrain. They were still able to live off their remaining land, but their margins were very slim. When President Diaz appointed the wealthy, frivolous Pablo Escandón as governor of Morelos in 1908, the hacendados abandoned whatever restraint they had previously exercised with the villagers’ land. Now they wanted all of it.

If Zapata, newly appointed as village leader, didn’t take a stand, his people would starve. So he gathered together 80 men with guns and told the hacendados’ armed guards that he had nothing against them personally, but the land they were guarding belonged to Anenecuilco, and they could see themselves out. Then he redistributed the plots equitably among the villagers and refused to pay rent on it. Thus, in quick succession, Zapata’s army and agrarian ideology were born.

When Madero released the tiger of revolution, Zapata united farmers who shared the plight of his people, with the sole objective of getting their land back so they could all go home. When Madero took office, Zapata thought the new president would return their lands in short order, concluding Zapata’s involvement in the revolution. To his great distress, Madero failed to comply, and Zapata was forced to once again leave the village for the battlefield. Though his subsequent victories imbued his name with power, the last thing he wanted was to spend the rest of his life as a simpering politician hobnobbing with elites in the nation’s capital. His aversion to Mexico City was so profound that when he occupied the city during the revolution, he stayed in a cheap hotel near the train station so he could return to Anenecuilco the very moment he could.

If the greedy planters of Morelos hadn’t directly threatened the villagers’ survival with escalating encroachment, or Madero had returned the Zapatistas’ stolen lands upon taking office, then history might never have known Zapata’s name.

Zapata may have been humble, but he was no ascetic. His commitment to his wife and family was undeniable, but it did not interfere with his having 16 children with nine different women, and pursuing amorous relationships with four more. As John Womack writes in his definitive biography, when he got married, “Zapata already had at least one child (by another woman) and no doubt assumed—it was a common male assumption—he would have many more by many women he cared about.” He was a snappy dresser; he favored elaborately embroidered sombreros, and his suit pants had silver buttons running up and down the sides. The people of his village were accustomed to seeing him dressed to the nines, riding through the countryside on a fine horse with a silver saddle. Women, horses, nice clothes—why shouldn’t Zapata include drinking on his list of moderate indulgences?

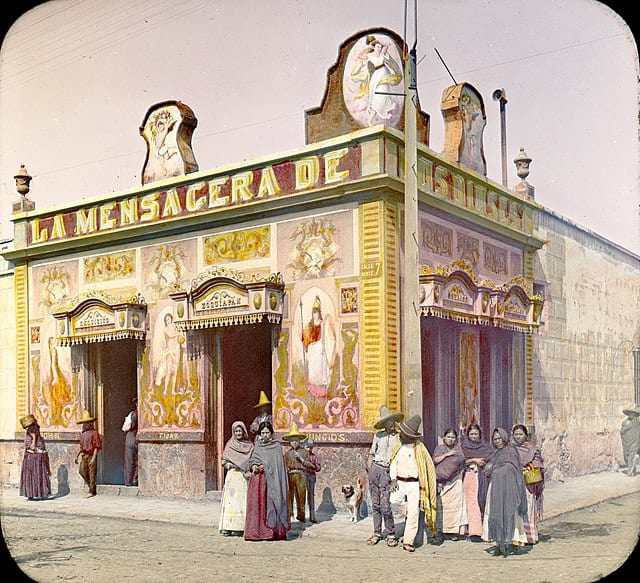

In fact, alcohol was very much a part of traditional village life in central Mexico. Pulque, the ancient indigenous beverage made from the fermented sap of agave, was consumed in great quantities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were more pulquerias in Mexico City than bakeries or butcher shops, and a study from around the same time conducted by representatives of Mexico’s burgeoning beer industry found that the average Mexican consumed 194 liters of pulque annually3 (more than double the quantity of beer consumed by the average German at the time). Pulque was considered by most to be a basic necessity, and part of a healthy diet; with its low alcohol content it was consumed frequently though not necessarily to excess. Liquor, by contrast, was comparatively rare.

Since the people of Morelos were so deeply tied to their land and community, alcohol didn’t pose a serious threat for most. After a long day in the fields, it’s hard to stay awake for late night carousing, and even if you overdid it the night before, you’d still have to get up early to farm alongside your family and neighbors. Drinking pulque at lunch and dinner only added zest to life, and serving wine and liquor for celebrations like weddings and births offered good-natured inebriation as a way to mark the occasion.

Nevertheless, the perceived dangers of pulque were a favorite target of the científicos4, the notorious technocrats determined to shape Mexican society according to the philosophy of Herbet Spencer, a key founder of scientific racism. With the typical paternalism of the Porfirian elites, pulque was portrayed as having degenerative effects on the lower classes—they even pointed to it as the primary cause of urban crime—and great pains were taken to curtail it. Government officials cracked down on pulquerias, levied high taxes on alcoholic beverages, and launched temperance campaigns to educate the population on its corrosive effects–though to little avail. Pulque had been a way of life for far too long to go down easy to the forces of elitist disdain.

Consider the position of a villager in the Zapatista army when confronted with the notion of pulque as Public Enemy No. 1, after a generation of watching ancestral lands disappear into the greedy hands of land-ravenous hacendados who were totally indifferent to whether or not he and his family starved to death. As the hacendado who first drove Zapata to armed resistance put it, “If that bunch from Anencuilco wants to farm, let them farm in a flowerpot, because they’re not getting any land, even up the side of the hills.5” It must have been painfully obvious to the working poor that the cientifícos’ framing of social ills according to their supposed character defects was little more than the upper classes’ veiled attempt to rationalize profiting from stolen land and labor.

But when it came to alcohol, the belief that it led to social corrosion didn’t always miss the mark. Among the bandits and desperados in the mountainous deserts of Chihuahua where Pancho Villa first made his name, drinking culture wasn’t always so benign. The haciendas in the north first cropped up to support the mines established by the Spanish, and they expanded under the Porfiriato. The debt peonage labor system they employed was close to slavery6. Hacendados held back the wages they owed their laborers, claiming that their living costs, provided for by the hacienda, outstripped the value of the labor. Often, hacendados were only too happy to provide alcohol alongside basic necessities. With addiction comes dependency, making the hacendados’ power nearly absolute.

In the 1890s, an international financial crisis forced many of the mines to close, leaving a large sector of the population unemployed. For increasingly impoverished northerners, alcohol offered an escape from their misery. Proximity to the US border also meant plenty of access to American liquor7, which lacked the nutritional value and ancestral connection of pulque.

Chihuahua was a volatile place in the years leading up to the Revolution. A skilled outlaw could make a plenty good living horse trading, smuggling, and rustling cattle, and banditry proliferated as the Porfiriato followed its course to collapse. Though the choice to live outside the law was often a response to an unjust system, the roving bands of well-armed thieves and cattle rustlers weren’t necessarily acting out of social consciousness. Banditry was a violent life by nature, and without self-restriction, bandits were dangerous. As historian Eric Hobsbawm writes in his study of social banditry as a precursor to revolutionary ideology, “Vengeance, which in revolutionary periods ceases to be a private matter and becomes a class matter, requires blood, and the sight of iniquity in ruins can make men drunk.”

Pancho Villa was a quintessential social bandit. Unlike Zapata, he was not born with land to lose; he was a sharecropper and hustling entrepreneur from Durango who turned outlaw at a young age after clashing with an hacendado over perceived injustice8. It’s hard to pin down definitive details of his life, since local legends, corridos, and the man himself all told conflicting stories. But at the time of the revolution, he had fled north to Chihuahua, where he skirted the law and did business through his a broad network of connections, which likely included the state governor, Abraham González. When González joined Madero’s movement, he recruited Pancho Villa as a leader in his revolutionary army.

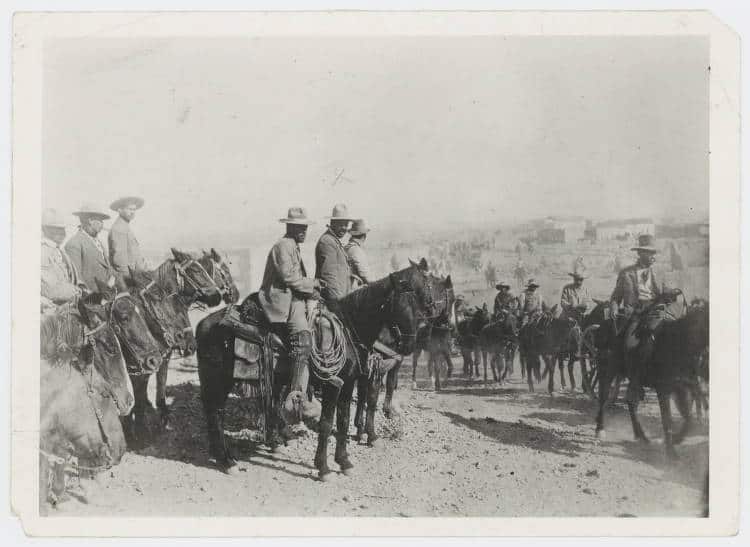

That Pancho Villa became the preeminent military leader in the north was in no small part due to his abstention from alcohol. To begin with, it took clarity and focus to execute the supremely clever tactics upon which he built the reputation of his División del Norte, from night raids to lucrative and bloodless train robberies. But most importantly, it sent a message to the people that they had nothing to fear from his armies. Under his leadership, civilians were not to be harmed—disorderly conduct on the part of his soldiers, especially while inebriated, would be punished with death.

By contrast, Villa’s ally-turned-rival Pascual Orozco had no such policy, and it quickly lost him much-needed popular support. As one eyewitness reported, drunken misconduct characterized the arrival of the Orozquistas in the city of Parral: “Their first work of destruction was to break into every store in which they believed alcohol could be found, and after the troops were drunk, things really began to warm up…They soon began to enter the houses asking for money, arms, jewelry, alcohol; they destroyed the furniture and caused panic among families. To underline their demands, these drunken men entered the living rooms with the safety catch pulled off their rifles.9” The news spread that Orozco had lost control of his troops, and the region began to sour on the man who once had been its most popular leader.

Meanwhile, the reputation of Villa’s army for gentlemanly conduct was growing. As another eyewitness in Parral commented, “The troops maintained perfect order, and absolutely no looting took place.10” This is not to say that hacendados could expect to hold onto their property when General Villa rode into town, but expropriations were targeted and conducted expediently, and never to excess. Villa kept very little for himself, and redistributed the wealth widely among the hungry people of the north, who showed their gratitude in endless songs written in his honor.

It was no mean feat to inspire ar army’s intense loyalty without the motivation of hooch and plunder. But by expropriating the assets of wealthy hacendados to feed his army and reward them for exceptional service, he demonstrated that he was ultimately on their side. “What further attracted many of Villa’s soldiers to him was that he was not aloof but attempted to establish as many personal links with them as he could and to show how much he cared for them,” writes Friedrich Katz in The Life and Times of Pancho Villa. “When a soldier was in urgent need of money for family purposes, he would go and see Villa, who would personally hand it to him.” And when his soldiers were hurt, they would be cared for by the state-of-the-art hospital train Villa had organized for his men.

Not only was he unstinting in providing for his people, Villa made a point of breaking bread with soldiers of all ranks. As Katz explains, “Frequently, Villa would suddenly turn up at one of the campfires where his soldiers were preparing their food. He would ask if he could join them and then sit down and partake of whatever they had prepared.” The significance of demonstrating his commitment to equality in a civil war defined by class struggle cannot be overstated. But it also served the purpose of letting his army know that they could expect to be observed by their leader up close at any time. Anyone hoping to end the night at the bottom of the bottle poured the first drink at their own risk, knowing that General Villa might pop by at any moment.

For while the people of Morelos were held to account by their obligations to the land and each other, nothing but the great General himself stood in the way of the northern soldiers’ disorderly conduct. Waging class war with an army of outlaws is a tough business, and if he wanted to restrain the ranks, he had to lead by example. Prohibitionist measures such as closing down the saloons and executing drunken officers11 were underscored by his own sobriety.

Not that abstaining from alcohol made him austere. In his writing on the Mexican Revolution, John Reed (a celebrated American journalist who rode with the División del Norte) depicts Villa as humorous, averse to pomp and circumstance, and forever searching out sport and comradery with the rank and file. “Villa never drinks nor smokes, but he will outdance the most ardent novio in Mexico,” Reed describes fondly12. “When the order was given for the army to advance upon Torreón, Villa stopped at Camargo to be best man at the wedding of one of his old compadres. He danced steadily without stopping, they said, all Monday night, all Tuesday, and all Tuesday night, arriving at the front on Wednesday morning.”

Clearly, Pancho Villa didn’t need to drink to dance two straight days before successfully securing the first great victory against Huerta. Similarly, when he met Zapata in Xochilmoco, there were surely other ways to bond. Both men rode horses beautifully. They might have taken long rides in the countryside, speaking only when it felt natural, and gradually discovering the ground beneath their common purpose. As men who were justifiably wary of betrayal, it would have taken time to learn to trust each other.

But time was something they just didn’t have. Their chief political opponent, Venustiano Carranza, had consolidated his power and was ready to trade in the chaos of the revolution for a return to order. If Villa and Zapata were going to forge an alliance strong enough to coordinate separate campaigns in the north and south, they needed to get on the same page, and they needed to do it fast.

It’s no secret that alcohol’s propensity to loosen inhibitions comes with plenty of pitfalls. But when you need to get intimately acquainted with someone in a hurry, there’s nothing better—if you struggle to drop your guard, a couple of drinks is all it takes to strip it from you. When the cognac failed to open that door, they desperately looked for some other point of connection. What they found was Carranza, whom they both had plenty of reasons to despise, and each of them expounded on the many faults of the fusty hacendado. Temporarily, at least, it did the trick. Their mutual hatred of the revolution’s least charismatic leader was ground enough for a shaky alliance.

But when the leaders parted company, the revolutionary coalition quickly fell apart. Divided, they were conquered. Soon after their defeat, assassins came for them both. And with them died the best chance Mexico ever had to dissolve the unyielding class structure that continues to hold the country in its grip.

Every major historical moment is a garden of forking paths, and it seems futile to contemplate what might have been. But if you accept the premise that a few drinks in Xochimilco might have changed the history of Mexico, the temptation to indulge in some speculative history is overpowering.

Let’s imagine that this time, when Zapata calls for cognac and Pancho Villa chokes on it, Zapata is struck by a way to salvage the moment. This meeting is between men of the people, not aristocrats—now is no time for fine imports. And for all that they are honored by the solemnity of the event, they have to admit that it’s making them both uncomfortable. “Look,” he says to Villa, leaning in. “Around the corner is a cantina—let’s excuse ourselves and head there to talk things over.” The restaurant isn’t big enough for their entourage, so they guard the entrance as the men sit down. The server is flustered but gracious, and brings them each a plate of beans and fresh, steaming hot tortillas. She disappears briefly before returning with a pitcher of pulque. Zapata pours, and Villa drinks it without thinking as the two of them crack jokes about Carranza while they muse over how best to hold Mexico City. They talk about the best terrain for a night attack, the privations of a long campaign, where to find the fastest horses in Mexico, and, by now on their second pitcher of pulque, women they have loved. All the while Mayahuel works her charms, and the men begin to see that while a common enemy is nice enough fodder, the ties between them run deeper.

The late afternoon sun streams through the window, and they decide to go out riding before it sets. The server shyly approaches with a bottle in her hand—vino de mescal, straight from the still. It’s her cousin’s best batch yet, and she offers it to the jefes for their journey. Later, as the sun sinks over the fields, Zapata hands Villa the bottle over the saddle. Away from all but the blazing eyes of the Attila of the South, Pancho Villa thinks to himself that it’s true what they say. In everything there must be moderation—including moderation.

- Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, John Womack ↩︎

- “La industrialización de México: historiografía y análisis”, Stephen H. Haber

↩︎ - Apuntes para la historia de la cerveza en México, Jean-Paul Krammer

↩︎ - La querella por el pulque : auge y ocaso de una industria mexicana, 1890-1930, Rodolfo Ramírez Rodríguez

↩︎ - Womack ↩︎

- “North American Peonage,” Andrès Reséndez

↩︎ - “Drinking difference: Race, consumption, and alcohol prohibition in Mexico and the United States,” Marie Sarita Gaitán

↩︎ - The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, Friedrich Katz

↩︎ - Katz

↩︎ - Katz

↩︎ - Katz

↩︎ - Insurgent Mexico, John Reed

↩︎

Leave a Comment